Blue Notes

Since its founding in 2012, Otoroku, the in-house label for the London venue, Cafe Oto, has become a crucially vehicle for documenting the activities of contemporary experimental music and beyond. Not long into their journey, the imprint expanded their modus-operandi to include reissues of long out of print, holy grails from the world of improvised music.

Their latest two releases, two towering documents from the South African ensemble, Blue Notes - 1976's “Blue Notes for Mongezi” and 1987’s “Blue Notes for Johnny” - fall into this later territory and are hands down some of the most important work the label has ever done. Truly singular and overwhelmingly moving gestures by some of the most remarkable and talented artists in the history of jazz, there’s nothing quite like them out there. Their reemergence in 2022, holds the potential to turn history on its head.

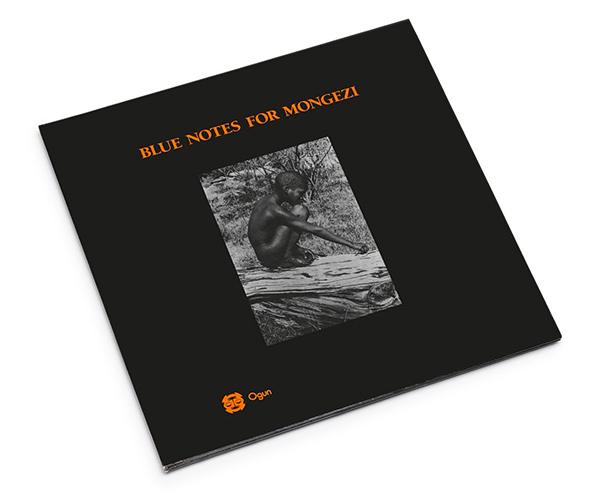

"Blue Notes for Mongei" (2LP, 1976)

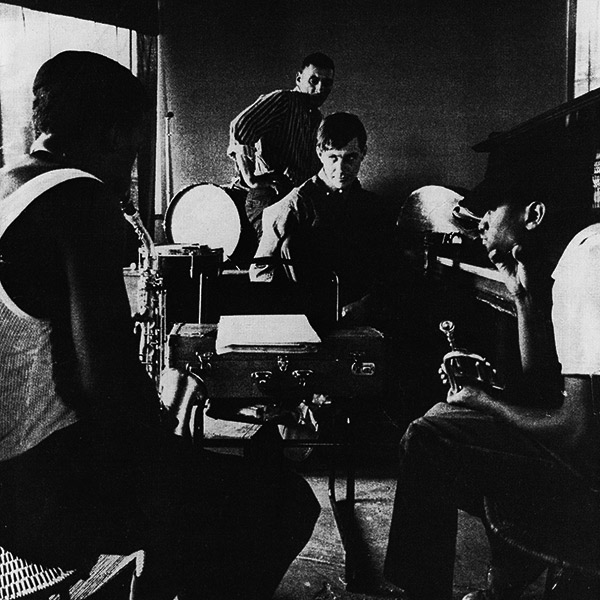

Founded in Cape Town in 1962, Blue Notes stand among the most important ensembles in the history of jazz. Artistically brilliant and groundbreaking - gathering, within a few short years, a devoted following that included Don Cherry, Steve Lacy, Abdullah Ibrahim, Dexter Gordon, Kenny Drew, Keith Tippett, Evan Parker, John Stevens, and numerous others - they were also the first widely visible multiracial band in South Africa, coming to prominence in 1963 at the National Jazz Festival in Johannesburg, where they immediately established themselves, as a definitive voice in Pan-African jazz.

As a mixed-race band under South African apartheid; this group of friends and like-minded artists - Chris McGregor, Mongezi Feza, Dudu Pukwana, Nikele Moyake, Johnny Dyani, and Louis Moholo-Moholo - existed within a context that viewed their mere existence as a dangerous and subversive act. In 1964, as the pressure mounted, they joined an exodus of musicians for Europe, eventually settling in London during the following year. Sadly, not long after arriving, facing continued economic peril, the group buckled. Johnny Dyani left to join Don Cherry’s band. Moholo-Moholo and Dyani followed suit and joined Steve Lacy on tour, while the remaining members morphed into a number of ensembles that eventually grew to become Chris McGregor's Brotherhood of Breath.

Following a decade of furious activity that had witnessed each of the Blue Notes working in numerous ensembles and often as band leaders, in late 1975, Mongezi Feza - in the midst of a fruitful period collaborating with Dudu Pukwana, Johnny Dyani, and Okay Temiz - suddenly passed away at the age of thirty from pneumonia. Nine days later, on the 23rd December, following the memorial service to their friend, Pukwana, Dyani, McGregor, and Moholo-Moholo gathered in a rehearsal room in London, and set out to play. Fittingly, no discussion took place before or during the session. The music was left to say it all.

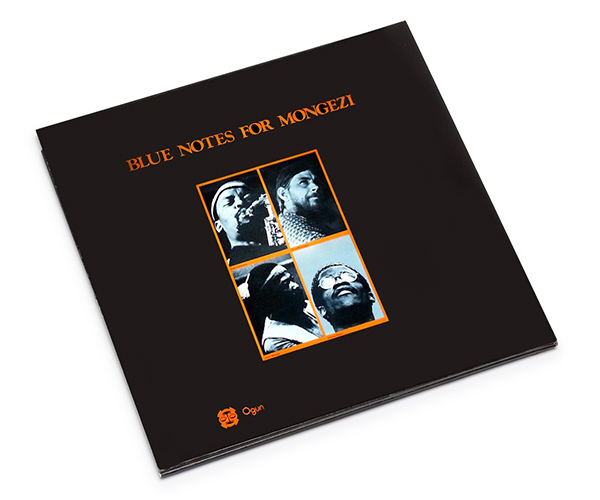

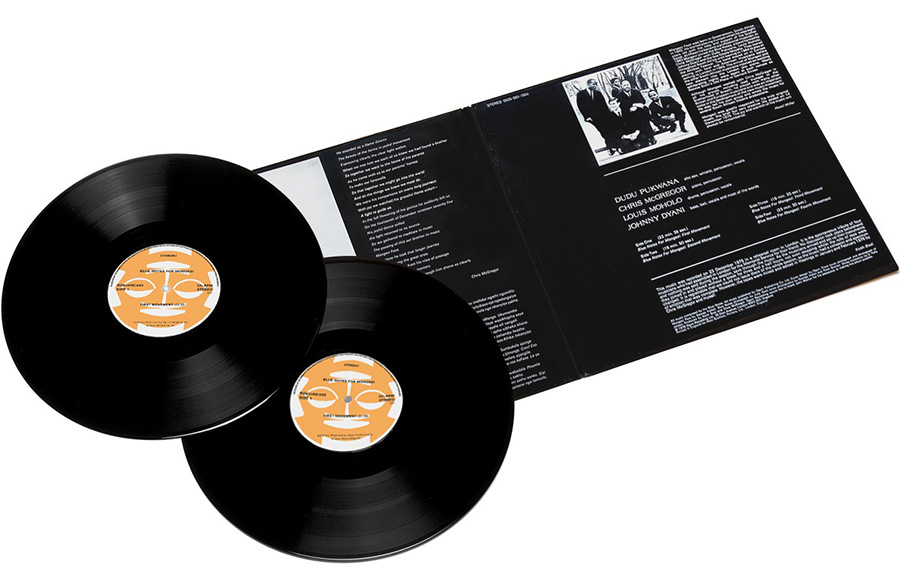

The resulting album, the double LP “Blue Notes for Mongezi”, released by Ogun early in the next year, coalesced into four long-form movements that occupy a side each, collectively unleashing an onslaught of free jazz fire, fluidly covering a remarkable range of moods and tactical approaches across its length. For anyone encountering the Blue Notes for the first time, the album must have felt like being blindsided by a brick, adding a profound sense of credence to Moholo-Moholo’s belief that free improvisation was intrinsically linked to the Pan-African temperament. In the band’s hands, the idiom sounds like nothing else and exactly as it should.

Recorded during a moment when Afrocentrism presented a firm hold within the free jazz scene - encountering many leading lights incorporating references to their African cultural heritage and roots into their music - prior the appearance of “Blue Notes for Mongezi” in 1976, possibly no other free jazz release had featured an entirely African ensemble, integrating an aural pallet so deeply connected to their own culture. It is, when viewed on these terms, arguably the most authentic document of the Afrocentric sound ever laid to tape.

A frenzied funeral dirge, a cry, and catharsis, as the four movements of “Blue Notes for Mongezi” unfold the ensemble rises and falls between playful and joyous movements of deconstructed song, rhythmic and vocal tribalism, and churning, instrumental free expression. It indicates not only a possible future for musical expression - as all truly avant-garde music does - but also the very roots of music itself, illuminating, through abstraction, the far-flung, ancient roots currently carried by the New Orleans “first line” march to the grave. It is a decidedly African vision of free jazz, coalescing as a collective expression of celebration and loss on a cold London day. It is a masterpiece unfolding in real time - out on a limb and laden with risk - created by four of the most talented voices the idiom has known.

Otoroku’s first ever reissue of “Blue Notes for Mongezi” - made with the full participation of Ogun, remastered from the original tapes, and beautifully reproducing the original 1976 sleeve - represents one of those rare moments of historical reappraisal and justice. It is quite frankly one of the greatest free jazz records ever made, and is impossible to recommend enough.

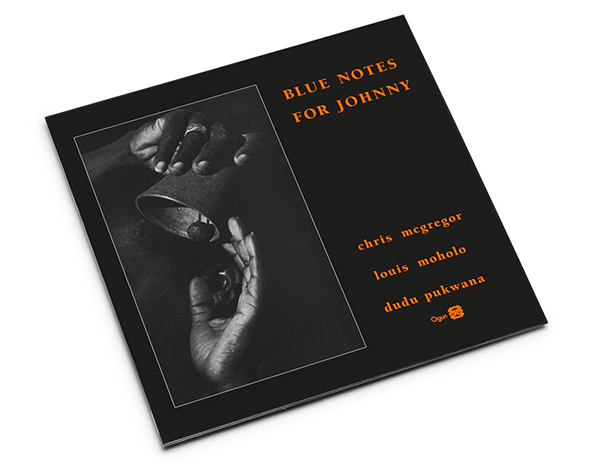

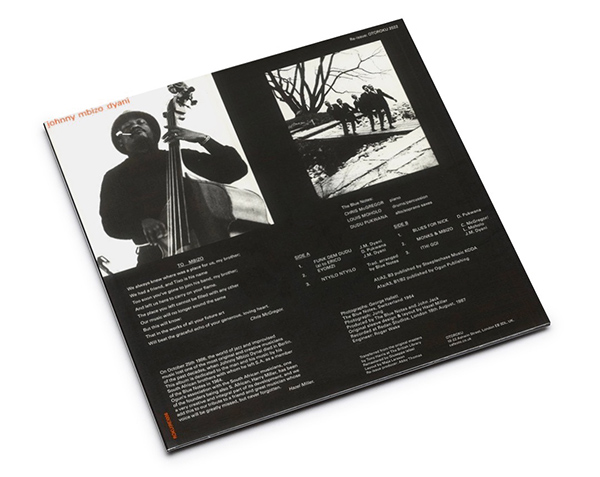

"Blue Notes for Johnny" (LP, 1987)

It seems Blue Notes found a deep sense of creative communication from the start. Even after their informal dissolution in 1965, the members contentiously came back together under different banners, producing some of the most striking improvised music of the 1960s and '70s. This became more pronounced following the recording of “Blue Notes for Mongezi”. During those years, Blue Notes entered a sporadic period of activity working under their original name, which culminated in 1987, following the untimely passing of Johnny Dyani in late 1986, when the last three members of the original line-up - McGregor, Pukwana, and Moholo-Moholo - reformed to pay tribute to yet another of their fallen brothers.

In the years since Dyani had left to join Don Cherry’s band in 1965, the bassist had become one of the preeminent figures in free improvisation, produced an astounding body of work as a leader, in numerous configurations with Moholo-Moholo, McGregor, Feza, and Pukwana, and in collaborations with Cherry, Okay Temiz, John Tchicai, Joseph Jarman, Don Moye, Khan Jamal, Noah Howard, David Murray, and others. His loss echoed deeply across the world of jazz, but nowhere was it felt more than it was among the tight knit group of friends that had come together against the odds in Cape Town between 1962 and 1963.

“Blue Notes for Johnny”, the group’s second musical memorial to a band member, is a very different affair from it predecessor. Where “Blue Notes for Mongezi” ride a tide of furious free jazz radicalism, the later - while no less visionary - incorporates a considerably broader range of touchstone and practices, nodding toward the band’s foundations in be-bop and post-bop, without abandoning where they had journeyed along the way. Internalising equal elements of hard-bop, modalism, and free improvisation, it is a startling creative statement, imbued with tension, that renders an equally radical and sophisticated challenge; a furious tide masquerading in gentler forms.

A celebration and a memorial. Joyous and tragic. A real time resurrection of personal experience, “Blue Notes for Johnny” dodges, dances, and transforms across its two sides, refusing to be nailed down. As the trio pushes against each other, bristling tonal and rhythmic collisions leave the impression that something is bound to explode, without ever fully letting go.

“Blue Notes for Johnny”’s memorialisation is unwittingly doubled by the fact that it captures the final time that the Blue Notes would come together in the studio. Both Dudu Pukwana and Chris McGregor would pass away three years later in 1990, leaving Moholo-Moholo - who continues to carve a groundbreaking trajectory across the world of jazz - as the last surviving member.

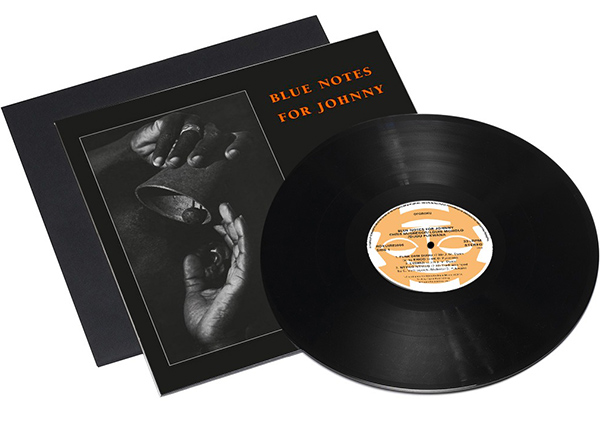

Like “Blue Notes for Mongezi”, “Blue Notes for Johnny” is an absolute triumph in the history of jazz. It was a proof, during the 1980s when most of this music found itself in less ambitious realms, that radical forms of creativity were still alive and well. Otoroku’s first ever reissue of “Blue Notes for Johnny” - made with the full participation of Ogun, remastered from the original tapes, and beautifully reproducing the original 1987 sleeve - represents an astounding and deeply historically important effort, bringing one of the greatest bands in the history of jazz the attention that they’ve always rightfully deserved.