Terry Jennings

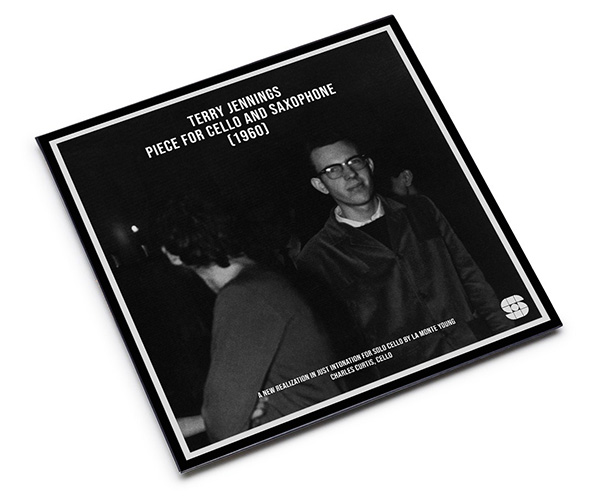

Since its founding during the mid 2010’s by the composer, Tashi Wada, the Los Angeles-based imprint, Saltern, has set the pace for the release of profoundly important historical works. Here at SoundOhm, a love affair was born on day one. Conceived as a means of support for artists working in Wada’s immediate circle, the power packed into the label’s small, carefully considered catalog of albums by figures like Charles Curtis, Morton Feldman, Simone Forti, and Yoshi Wada has few parallels in the contemporary landscape of adventurous sound. Despite their towering accomplishments to date, their latest, “Piece for Cello and Saxophone”, by the long overlooked early minimalist, Terry Jennings, is possibly their most historically important release to date. Realized by Charles Curtis, in close collaboration with La Monte Young, and issued as a beautiful double LP, complete with a four-page insert with liner notes by Young, Curtis, Anthony Burr, and Tashi Wada, it’s stunningly beautiful on countless terms, bringing one of the great minimalist pioneers the attention and care he’s always deserved.

Long dominated by a handful of names - Young, Riley, Reich, Glass, etc. - over the last few decades, the canonical narratives of Minimalism have begun to slowly expand, offering a more complex image of how this music came into being. First came the reissue of Tony Conrad and Faust’s “Outside the Dream Syndicate” in 1993. Then Charlemagne Palestine's “Strumming Music” returned two years later, followed by a host of Henry Flynt’s archival work. Despite having been relatively forgotten for decades, it turned out that all of these artists had been there from the start. During roughly the same moment, interest in the work of artists like Éliane Radigue, Phill Niblock, Jon Gibson, Jon Hassell, and Pauline Oliveros began to percolate, contributing to the reshaping of historical happening. Even more recently, the work of sinfully overlooked composers like Richard Maxfield and Dennis Johnson has emerged, opening new windows into minimalism’s earliest days. The subject of Saltern’s latest release, the composer Terry Jennings, is among the most important of the pieces of the puzzle yet to have emerged.

Terry Jennings was a foundational member of musical minimalism. At the age of 20 in 1960, 9 of his works were presented at Yoko Ono’s legendary loft series, along with his close friends Richard Maxwell, Terry Riley and La Monte Young. Young once referred to the composer as “the most talented musician I know.” Riley described him as “a musician of great originality and expressive power”, and praise didn’t stop there. Cornelius Cardew and John Tilbury were devoted fans, and he performed regularly with John Cale and Charlemagne Palestine, in addition to being an early member of The Theatre of Eternal Music. Yet, tragically, within the broad understanding of the history of minimalism and its development, Jennings - one of its pioneers and leading lights - is conspicuously absent, partially due to a temperament that shied away from self-promotion and life-long drug addiction that contributed to his untimely passing at the age of 41 in 1981.

An incredibly talented saxophonist, glimpses of Jennings can be caught on historical recordings of the Theatre of Eternal Music, and by Richard Maxfield and John Cale, but sadly, during his lifetime, no releases of his music ever emerged. Later, two of the only instances of Jennings performing his own work came to light; one capturing a collaboration with Palestine, entitled “Short and Sweet”, with the second being a performance with Charlotte Moorman of “Piece for Cello and Saxophone”. The rest has been left to others; Jon Gibson’s rendering of “Terry's G Dorian Blues”, John Tilbury’s recordings of a number of piano works, and a small handful of others.

“Piece for Cello and Saxophone”, composed in 1960, is a particularly important work. An early version of it was performed in the aforementioned series at Yoko Ono’s loft, and it is one of only two available works we have by Jennings where we can witness his own realization. The evolution of its current form by Charles Curtis, began in 1989 in preparation for a memorial concert at La Monte Young’s MELA Foundation, where Curtis and Young developed a version to be played by the former on cello, with the latter singing, rather than on saxophone (Young’s original instrument). Just under a decade later, Curtis developed a version for solo cello, enabled by the openness of Jenning’s original score, which is the incarnation featured on Saltern’s release.

Clocking in a just under an hour and a half, stretching over four glorious vinyl sides, “Piece for Cello and Saxophone”, in Curtis’ incredibly sensitive and adept hands unfolds a work of glacially paced long tones, imbued with a profound emotive presence; almost as though his cello was weeping in slow motion. Particularly when viewed in its historical context - the early days of minimalism’s fracture with the proceeding generation’s clinical temperaments and atonality - the potency of the work’s statement is impossible to ignore. Not only is it beautiful and harmonically rich with glistening tonal relationships, but it feels bound to an ancient continuum of music making and human expression; looking beyond the European canons of classical music toward the traditions of India and beyond. Like Hindustani music, if feels draws upon time, experience, and the evocation of specific emotion, as though the music itself is cocooning the listener in the composer’s inner world.

Slowly shifting, sliding, and evolving across the album’s length, “Piece for Cello and Saxophone” is unquestionably one of the most evocative and sorrowful works of early minimalism yet to have emerged, unveiling a profound talent at the very center of the movement’s development. There’s quite frankly nothing like it out there. As ever, Curtis’ playing, guided by unparalleled skill and sensitivity, is second to none. There could be no one better to bring the piece back into the world. Possibly the most historically important release of the year, and an absolute joy in listening, Saltern’s double LP release of Terry Jenning’s “Piece for Cello and Saxophone” was pressed at RTI to achieve the highest possible level of fidelity, complete with a four-page insert with liner notes by La Monte Young, Charles Curtis, Anthony Burr, and Tashi Wada.