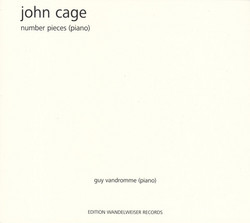

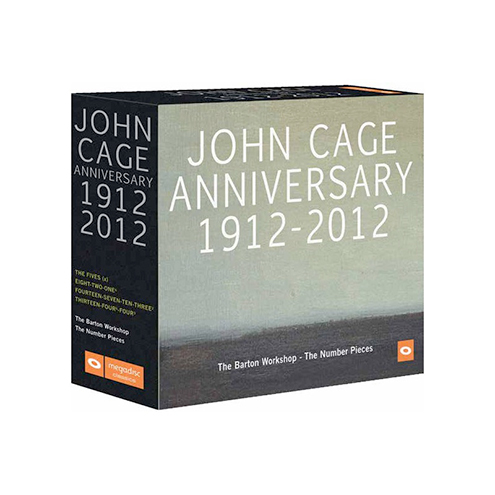

John Cage

John Cage Anniversary 1912-2012, The Number Pieces

Some of the most mysterious and meditative pieces by the legendary John Cage’s (1912-1992) performed by The Barton Workshop, an Amsterdam-based ensemble founded by the legendary American composer-trombonist James Fulkerson. Number Pieces, fortyeight in all, belong to the final six years of his life. They are so called because their titles, plus the actual construction of each composition, are based on numbers. They were created with the aid of software designed by Andrew Culver who had worked with Cage on many occasions previously. This enabled Cage to work quickly and thus fulfil the many commissions that came his way as a father figure of experimental music. This CD presents three of these compositions.

The number pieces as a whole suggest a strange kind of alchemy. The raw materials are: single sounds usually made on musical instruments, time brackets in which performers are invited to place sounds where they chose within prescribed limits, fairly prescriptive performative tasks which never the less allow some freedom of action, either continuous undifferentiated textures (in the larger pieces such as Fifty-eight from 1992 or One Hundred and One from 1988) or pieces for smaller ensembles involving appreciable silences. These materials, fluidly fixed and thus inviting interpretation, are placed in a crucible which consists of the overall length of the piece, the performers and thus, of course, the performance itself. The uncompromising raw materials – hardly the stuff of the instrumental and multimedia circuses Cage was known for from the late 1950s onwards (Piano Concert -1958, HPSCHD –1967-9, Roaratorio - 1979) – somehow come alive, each piece in its own special way. Given the similarity of method, and often materials too, the diversity of these number pieces is remarkable.

On this CD, for example, Four6 calls for extended techniques and non-standard sounds, whereas Thirteen is played by conventional chamber/ orchestral instruments producing standard musical sounds some combinations of which are extraordinarily beautiful by any yardstick. Four3 calls for a number of rainsticks, but also gives performers scraps of melody extracted, by chance methods, from Erik Satie’s Vexations – a single page of meditative music repeated 840 times, thus lasting roughly eighteen hours, and a spiritual favourite of Cages.

Cage’s aesthetic, based as it was from the early 1950s onwards on the use of chance, was extraordinarily fertile but also creatively contradictory. His practice was to objectify sounds so that personal taste (his own or a performer’s) was removed from the equation. Yet, with the exception of a few tape pieces, his music has to be performed by human beings who, as it happens, are nearly always called upon to do more than simply read off a score. (Exceptions would be Music of Changes of 1951/2 or the various virtuoso etudes written in the late 1970s). Performers are not asked to improvise – Cage was suspicious of the expressionist tendencies of freeform improvisers in particular – but neither are they automatons obeying orders. For example, pianists playing the elaborate graphics of the solo part of the Piano Concert actually bring much of themselves to the realisation of Cage’s complex instructions which, with familiarity, often turn out to be imprecise. The result – and this is true of many of his pieces from the 1950s through to the early ‘80s – is a strange agreement between on the one hand constructivist, objectified sound and, on the other, audibly subjective human agency. The term “abstract expressionism” actually springs to mind no matter how much Cage would have rejected the idea of expression in his music. It also suggests the “all over” approach to composition typical of painters Mark Tobey or Jackson Pollock.

Before the number pieces Cage’s compositions tended to veer one-way or the other – tightly objective (Freeman Etudes – 1977-90) or subjective (the Variations series). The highly subjective Piano Concert is a theatrically ironic kidnapping of concert tradition in which the performers have a ball in a tsunami of extended techniques – slides, squeaks, harmonics, rasps, bangs, grunts and farts – all best played deadpan although clearly hilarious at times. Likewise the Variations series, with their assemble-yourself kit-like scores, only superficially suggest a cooler, constructivist approach. The well-known Cage-David Tudor recording of Variations IV (1963) demonstrates a clear case of choices being made outside the orbit of the musical score. No actual sounds are proscribed in the score, only the placement of sounds in space. Therefore the inventive human agencies of Cage and Tudor were brought into full force resulting in a riot of simultaneous broadcasts, gramophone records, and other supposedly neutral sound sources.

The number pieces offer all some solutions to some of Cage’s dilemmas as a composer. Although performers are not invited to improvise, the narrowly proscribed notated limits to their actions turn out to be quite broad. The placement of a sound within a time bracket, for example (i.e. play a sound to begin after 1.00 and finish before 1.57) may be read as a chance to consciously participate in the formation of texture and thus the general effect and aesthetic of the piece. It is impractical to take taste, memory and ego out of this. Thus the expressive nature of music makes an open return to Cage’s works rather than being guiltily snuck in via the back door. It is this sense of a highly controlled framework populated by sounds that audibly “breathe” that characterises the number pieces.

Thirteen in particular, illustrates another reconciliation arrived at by the late Cage– his final acceptance of harmony. He called it “anarchic harmony”. Functional harmony, the kind that was the motive force of classical music, always led somewhere. Due to its elaborate system of leading tones, one chord inevitably implied the next – or, at least, a range of possibilities. For Cage this meant that the music never rested in the present but was always going somewhere, pressing on and on. His dislike of this suggests a world of alternative spirituality and anti-political critique. In the number pieces the simultaneous sounding of long held notes does create harmony (chords) often sensuous and pleasurable, but not a drive towards the next moment. Cage referred to what he called: “A changed definition of harmony; one that doesn’t involve any rules or laws. You might call it an anarchic harmony. Just sounds being together.”

He was delighted to find that “everything is harmonious and, furthermore, that noises harmonize with musical tones. (So he did see the difference!) And that gives me – I can’t tell you – almost as much pleasure as the macrobiotic diet”.

These two elements – some performer choice alongside anarchic harmony – make the number pieces a metaphor for Cage’s ideal society – freedom within agreed limits, activities of all individuals “interpenetrating but not obstructing” as he often said, and these leading to a general absence of striving or competition and thus centralised power. Unlike political composers such as Hans Eisler, Cornelius Cardew or Ewan MacColl, Cage embodied his political visions and beliefs in the very construction and realisation of the music rather than in propagandist texts.

In many ways the number pieces are wise solutions to the challenges presented by Cage’s aesthetic and methods over a period of roughly thirty years since he adopted chance as his major compositional tool. Previous solutions had been provocative, jokey, complex, clever, curious, smart, never lazy. The number pieces display the wisdom of an elder. They lay open the truth of Cage’s use of chance – a truth he would never have denied – that he fixed his chance procedures to obtain the results he wanted. Thus each piece has a clear identity conceived and created by Cage doing what composers had always done:

imagining music and writing it down. Chance then governs the note-to-note details of each piece, but the performers’ subjectivity is then drawn in the complete the picture. Four3, for example, with its rainsticks, sine waves, violin, piano and scraps of melody is distinct and unique, and could never be confused with the entirely pitched anarchic harmonies of Thirteen.

How to listen to these pieces? I would put it this way. There are many types of Zen: Rinzai, Soto, beat, everyday cliché and Cage Zen. Cage Zen would regard each of his pieces as an object of contemplation in which the mind is invited to focus on but not grasp each sound as it drifts by. By providing no climaxes, no conclusion and no audible logic the mind and ears are free to appreciate what is. As Cage once punned: “Happy New Ears”. Sam Richards

“Thirteen” (1992) for Flute, Oboe, Clarinet in Bb, Bassoon, Trumpet in C, Tenor Trombone, Tuba, 2 Percussions, 2 Violins, Viola, Cell

“Four6” (1992) for any way of producing sounds

“Four3” (1991) [EXCERPT] for four performers (one or two pianos, twelve rainsticks, violin or oscillator and silence).

“Five” (1988) for any 5 Instruments (Version for 5 Clarinets)

“Five [2]” (1991) for English Horn, 2 Clarinets, Bass Clarinet and Timpani

“Five [3]” (1991) for Trombone and String Quartet

“Five [4]” (1991) for Soprano Saxophone, Alto Saxophone, and 3 Percussion

“Five [5]” (1991) Flute, 2 Bb Clarinets, Bass Clarinet and Percussion

“Fourteen” (1990) for piano, flute/piccolo, bass flute, clarinet, bass clarinet, horn, trumpet, 2 percussion, 2 violins, viola, cello, bass.

“Seven” (1988) for flute, clarinet, percussion, piano, violin, viola, cello

“Ten” (1991) for flute, oboe, clarinet, trombone, percussion, piano, 2 violins, viola, cello

“Three2” (1991) for 3 percussionists.

“Eight (1991) for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, trumpet, trombone, tuba

“Two” (1987) for flute and piano Jos Zwaanenburg, flute - Frank Denyer, piano

“One4” (1990) for solo drummer Tobias Liebezeit, drummer

The Barton Workshop James Fulkerson, director, with John Anderson Clarinet, Bass Clarinet Andries Boelens Oboe Laura Carmichael Clarinet Frank Denyer Piano James Fulkerson Trombone Nina Hitz Cello Marieke Keser Violin Wim Konink Percussion Tobias Liebezeit Percussion Gertjan Loot Trumpet Eleonore Pameijer Flute, Piccolo Jacob Plooij Violin Elisabeth Smalt Viola Jos Tieman Bass Joeri de Vente Horn Jos Zwaanenburg Flute, Electronics