We do require your explicit consent to save your cart and browsing history between visits. Read about cookies we use here.

Nick Soulsby

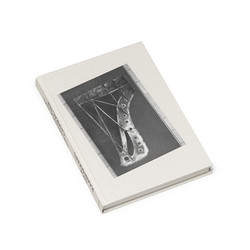

Everything Keeps Dissolving: Conversations With Coil (Book)

Nearly 600 pages! Black & white printing, Perfect bound, Softcover. In this heavily illustrated compendium, the legendary British experimental band Coil tell their story in the present tense, as events unfold across their twenty-year history. Between 1983 and 2004 the legendary British experimental band Coil established itself as a shape-shifting doyen of esoteric music whose influence has grown spectacularly in the years since its untimely end. With music that could be dark, queer, and difficult, but often retained a warped pop sensibility, Coil’s albums were multifaceted repositories of esoteric knowledge, lysergic wisdom and acerbic humor. In Everything Keeps Dissolving, core members John Balance and Peter Christopherson tell Coil’s story in the present tense, and from their personal perspectives.

Accompanied by their various collaborators, Coil describe the fertile eruption of ideas, inspirations, and stray tangents that informed their lyrical and musical visions—as well as those dead paths and castoff concepts that didn’t take root. Not only a worm’s eye view of Coil, these interviews provide insight into the late twentieth century’s evolving British cultural underground as channeled through two of its most astutely mercurial minds.

A milestone in Coil’s evolving posthumous history, Everything Keeps Dissolving contains a number of previously unseen drawings, photographs and other images by, and of, the band..

While John Balance’s childhood memories dwell on untethered physical relocation, astral connections, a sense of becoming ever more who he wished to be, Peter Christopherson’s early life – at least as he described it – was far more steady… But it’s hard to know. From the time he joined Throbbing Gristle through his time in Coil, Christopherson tended to shy away from interviews, often occupying himself elsewhere, or staying in the background. This discretion is visible in the way his collaboration with one natural possessor of the spotlight, Genesis P-Orridge, gave way to another in Balance. In many ways, Balance was his perfect emotional match: one helplessly exposed, the other firmly repressed. A focus on this gap between public and private faces is critical to Christopherson’s work which delighted in poking at society’s squeamishness. His nickname — Sleazy — resulted from what he described in Simon Ford’s Wreckers Of Civilisation as a youthful taste for “using the body as an object of fetishistic exploration…” His personal inclinations rubbed up against an ever more stifling cultural climate in which he witnessed P-Orridge charged for ‘obscene’ mail-art; the hysterical condemnation of Coum Transmissions’ Prostitution show; and police raids on Throbbing Gristle’s studio.

Hostile officialdom was a perturbing presence throughout Coil’s first decade. Balance spoke of being subject to police stop-and-search; of a friend’s flat searched for drug paraphernalia; of being arrested at a gay rights protest; of fear of the police leading to the cessation of Psychic TV and Coil’s exploration of cults. The 1987 Operation Spanner raids and prosecutions — for consensual sadomasochistic acts —heightened tension, then everything erupted in 1992 when a documentary made unfounded allegations of child abuse against P-Orridge. P-Orridge and family fled into exile as the police raided their home and confiscated their archives. Coil described being so scared they sanitised their home of anything that might arouse police suspicion and spent several years expecting the front door to be kicked in.

This was not the only existential threat to Balance and Christopherson. Both participated enthusiastically in the libertinage of London’s gay scene, only to be slammed brutally into the burgeoning devastation of AIDS. Personally escaping infection brought limited relief as they witnessed friends succumbing. Madonna’s tour manager, Martin Burgoyne, died on his 23rd birthday in 1986 with Balance musing: “you start to dwell on it, y’know? Especially if you’ve had sex with him.” Balance still sounded angry in 1995 over the death of Eddie Cairns, the cover artist for the ‘Tainted Love’ single: “I think it was Hammersmith Council who dealt with Eddie’s body… men in bloody Dalek suits, wrapped the body in numerous sheets of plastic and didn’t know how to deal with the body.” Their friend Leigh Bowery would die, aged 33, in December 1994. Meanwhile their long association with Derek Jarman was lived in the shadow of his HIV diagnosis in December 1986, until his death in February 1994.

Coil, and the wider gay community, reeled in shock with Scatology’s nod toward niche pleasures giving way to Horse Rotorvator’s explicit grappling with death as a lived experience. A U.K. resident in their 20s might experience an elderly relative’s demise, a further few an untimely loss from disease or misadventure… But to have so many young friends die, the terror of that time is underappreciated. In 1986, Balance was 24, Christopherson was 31: their peak years of sensual exploration were derailed by risk, sickness and death.

Beyond AIDS lay further trauma. ‘Ostia (The Death Of Pasolini)’ was a simultaneous tribute to the murdered film director; to a friend, Wayne, who jumped from the Dover cliffs; and to Leon, whose cause of death Coil left undisclosed. Again, in 1992, a voicemail recounting someone’s suicide, “…he threw himself off a cliff…” was the basis of the haunting ‘Who’ll Fall’. The recording was revisited for 1993’s ‘Is Suicide A Solution?’ with a cover image taken from the bedroom of a Coil fan who leapt from the window to his death. Their other 1993 single was ‘Themes For Derek Jarman’s Blue’, the film visually described blindness arising from AIDS.

Instead of relief from the numbing drumbeat of death, from emotional baggage, from the policeman’s shadow, the years around Coil’s third album proved a personal cataclysm. Described as their ‘dance’ album, Love’s Secret Domain was no testament to Second Summer of Love joyousness. In a vast release of tension, Coil spent much of 1988 – 1992 immersed in the hedonistic relief of Ecstasy and other drugs. The resulting album opened with ‘Disco Hospital’ — a metaphor as pointed as Coil’s ‘Tainted Love’ — then dwelt throughout on the intertwining of death and love, a soundtrack to desperation not delight. The chemically-induced fallout of these years was so severe it propelled Stephen Thrower from the group, while Balance collapsed on occasions both public and private, ultimately lapsing into alcoholism*. Marking the seriousness of this moment, ‘Eskaton’ became a permanent Coil label imprint. Eschatology — the study of the world’s end — tied together Horse Rotorvator’s explicit theme, as well as being a wordplay on Scatology. This loop acknowledged that Coil were beginning anew, that their past was linked to, but distinct from, their future. They lived now in the ‘last days,’ somewhere amid or beyond the apocalypse.

Balance and Christopherson sought workable ways to continue… But Coil, for a time, was too bloodied an entity to be the vehicle. Practically speaking, the name Coil existed from 1994 to 1998 almost entirely as an archive, a host for alternate identities, or a remixer of others’ work. Instead, a tentative step forward was taken by standing in direct opposition to their former self: 1994’s Coil Vs. The Eskaton and Coil Vs. ELpH singles. This led to the even more radical idea of shedding Coil’s damaged husk and splintering into new, unsullied personas: Wormsine, Black Light District, Time Machines, ELpH, Eskaton. 1995 – 1999 was an escape attempt: seeking refuge in a ‘black light district,’ the opposite of a red light district’s carnality; channelling alien entities to extirpate their own voices; escaping time altogether; rejecting Mars and the sun in favour of the feminine moon; leaving the dense metropolis in the east for a seaside town to the far west.

A mooted album title Coil had rejected ten years prior, Funeral Music For Princess Diana, seemed eerily prescient in 1997. It’s real significance, however, was as a mirror. Across their first decade, Coil tried to find ways to live amid trauma, then spent its aftermath shedding their identity to try to find the renewal that self-definition had given Balance as a young man. The final phase of their existence felt like a surrender. Tales of Balance’s frightening battle with alcohol were not products of a scandal-hungry media: Coil were the source. Alongside their candid interviews and on-stage acknowledgement of issues, by 2000 they were selling a blood-smeared ‘Trauma’ edition of Musick To Play In The Dark 2, then Balance performed in a straightjacket in 2004. Coil were not virgins. They understood the public’s appetite for salacious consumption, that the media was a delivery mechanism for perusing human pain, and they colluded in the same symbiotic relationship that ended Diana. While Christopherson gave every appearance of being ready to settle into being a musical elder statesman, Balance seemed harrowed by the prospect that he had no way out of his role as public avatar of pain.

[*There’s one further possibility I will voice. Aspects of Balance’s magickal pursuits encouraged the loss of personal identity as a step to greater knowledge. Balance made a point in the 80s of disparaging magickians he felt were too public in their work, stating that real forward motion should be achieved in private. It makes it hard not to wonder if this series of collapses, in which Balance described having forgotten his name and identity altogether, were in some ways aimed for, the visible outcome of private pursuits and intentions, even if the consequences were in no way predicted or desired.]

Related products

Become a member

Join us by becoming a Soundohm member. Members receive a 10% discount and Free Shipping Worldwide, periodic special promotions and free items.

Apply hereSoundohm is an international online mailorder that maintains a large inventory of several thousands of titles, specialized in Electronic/Avantgarde music and Sound Art. In our easy-to-navigate website it is possible to find the latest editions and the reissues, highly collectible original items, and in addition rare, out-of-print and sometime impossible-to-find artists’ records, multiples and limited gallery editions. The website is designed to offer cross references and additional information on each title, as well as sound clips to appreciate the music before buying it.

Soundohm is a trademark of Nube S.r.l.