We do require your explicit consent to save your cart and browsing history between visits. Read about cookies we use here.

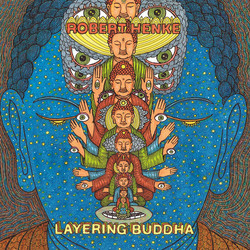

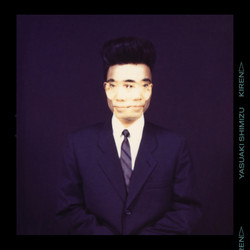

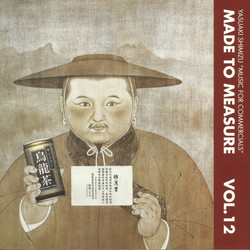

The unreleased 1984 follow-up to the groundbreaking albums Kakashi and Mariah's Utakata No Hibi, Kiren is Yasuaki Shimizu's work for experimental dance music. Employing cutting edge production to create lush new wave soundscapes, it bridges the gap between his early 80s recordings and his later work with the Saxophonettes, filling a key lost chapter in his discography. Full liner notes in English and Japanese by Chee Shimizu.

Yasuaki Shimizu’s endless curiosity has fueled decades of tireless creative endeavors. As a child, he learned to play multiple instruments—violin, clarinet, piano, guitar, percussion—but landed on the saxophone as his primary vehicle for expression. Ornette Coleman and Rahsaan Roland Kirk would influence his playing, but he soaked up all the musical education he could. Radio in hand, he’d dial in from his home in the Japanese countryside to hear sounds from across the world: chanson and flamenco, rock and canzone, music from Africa and music from the Middle East. He loved it all, but could just as easily walk to nearby rice paddies and revel in the insects orchestrating their own song. Nothing was off limits, which meant everything could inspire. As he grew older, local record stores would import more sounds from overseas. He never dared emulate them, though: “[I] had no interest in imitating that genius,” he once confessed. “I perceived it more as a way to expand my own sonic vocabulary.” He was determined to carve his own path.

By the late 1970s, Shimizu’s musical voraciousness allowed him to work in a variety of modes. He was part of hard-bop and jazz-fusion ensembles, contributed to classic city-pop records like Taeko Ohnuki’s Sunshower and Minako Yoshida’s Monochrome, and produced pop albums for singers like Yumi Murata and Naomi Akimoto. There was the Saxophonettes, originally conceived as a solo project to create moody renditions of American jazz standards. He also had his band Mariah, which served as an especially productive testing ground—their four records contain everything from prog-rock epics to dreamy exotica, new-wave freak-outs to art-pop brilliance. The LPs under his own name are numerous, but Kakashi and Music for Commercials are major standouts: The former is a thrilling crystallization of his poppier, melodic inclinations while the latter is a collection of ambient vignettes that feels like a proto-Donuts. Somewhere in the middle of all this is Kiren, a hitherto unreleased studio album from 1984. Another testament to his unbridled ambition, it’s mesmerizing for newcomers and longtime fans alike. Kiren stands out for more than just its sonics. Unlike most of Shimizu’s releases, it wasn’t intended for a record label. Instead, it was the product of the freedom he had while collaborating with Aki Ikuta, the late producer who was instrumental to his music’s sound. You can hear his boundary-pushing ideas on “Momo No Hana.” It begins with an extended passage of queasy ambience before Shimizu throws in additional noises to subvert expectations: high-pitched synth tones, a spectral growl, and a noise that sounds like a warped Banjo-Kazooie voiceline. Then there’s an instrument that recalls his affection for Indian classical music, and then a plunderphonic loop that anticipates Oneohtrix Point Never’s Replica shockingly well. “Ore No Umi” is just as bewildering. It has this chintzy guitar loop low in the mix.

A marimba quietly enters, and then the song charges forward with a minimalist pulse. Like the glam-rock pastiches found on early Mariah records, “Ore No Umi” thrives on a winking playfulness, though here it’s with a riff on Steve Reich—Shimizu approximates his ideas for a single element in this tapestry of layered rhythms. Anchored by a tumbling beat and bursts of sax, it’s triumphant and fun and a revelatory depiction of Shimizu’s ingenuity. WATCH Explore Fleet Foxes’ Self-Titled Debut (in 5 Minutes) As Shimizu recently told Bandcamp Daily, he considers Kiren part of a trio including Kakashi and Mariah’s Utakata no Hibi. He was on a real hot streak at this point in his career. On these three albums, recorded between 1982 and 1984, Shimizu was increasingly coming into his own; Kakashi is more progressive than the jazz excursions of 1981’s IQ-179, and Utakata no Hibi is considerably more cohesive than the first three Mariah records. One could compare those two LPs to other new wave-inspired art-pop acts from Japan—Chakra or Haniwa-Chan or Jun Togawa’s Yapoos—but with a stronger emphasis on rhythm, atmosphere, and texture, rather than pop songwriting. Kiren might be considered a culmination of these ideas, but funneled into a wholly instrumental album. He describes it as “the dance inside the image of myself,” and on the longform percussion-based jam “Kagerofu,” its patient unfurling and rhythmic insistence feel like he’s peeling back layers to get to his musical core. Shimizu’s musical identity, though, was constantly expanding. Even on this dance-focused LP, he arrived at his goal from different angles. “Peruvian Pink” is one of the grooviest songs, but it barely contains percussion. Instead, its foundation is a slick bassline and a repeating synthesized warble. As he plays sax in varying degrees of intensity, the music becomes increasingly cinematic, like a slow-motion montage via deconstructed boogie.

“Ashita,” on the other hand, takes the post-punk tendencies he’d explored in the past and makes them tastefully carnivalesque, letting squelching rumbles and marimba melodies take center stage. Elsewhere, “Asate” employs a robotic lurch while “Shiasate” shoots for exultant, regal glory. Across these seven tracks, Shimizu homes in on a sound that bridges his numerous interests. He looks back fondly on this era: “At that time, I could recognize that all of the various scattered elements I had been interested in since I was a child were collecting together inside of me, and becoming a single organic material.” His description of this album as living is illuminating—particularly given that it remained hidden from public ears all these years. Shimizu spent his entire life invigorated by sounds from around the world; with Kiren, he was able to partake in this ecosystem, to contribute something that was unmistakably his own.

By 1984, the Japanese composer, saxophonist and producer Yasuaki Shimizu was on a creative tear. Two years earlier, Better Days released his algorithmically acclaimed and eternally intriguing solo album "Kakashi", which served as a set-up for "Utakata No Hibi", the third and best album from Shimizu's folkloric synth-pop project Mariah. If history had gone slightly differently, the release of "Utakata No Hibi" would have been followed by an album of hyper-prescient experimental dance music titled "Kiren." However, due to a lack of interest in "Kakashi" at the time, that run was not to be. Instead, thirty-eight years later, "Kiren" has emerged from the archives through a plush vinyl, CD digital release on New York's excellent Palto Flats label, also home to reissues of "Kakashi" and "Utakata No Hibi".

Where "Kakashi" and "Utakata No Hibi" are albums that slowly found a global audience over decades through enthusiastic record store clerks, tapped in specialist radio shows, the mysteries of the YouTube Algorithm, and later on, social media, "Kiren" emerges in 2022. Although it's untethered from the weight of all of the above, by virtue of being what it is - an unreleased album from a true legend of Japanese music - expectations were always going to be skyscraper high; or at the very least, high. Thankfully, over the course of the seven songs included, the 1984 version of Shimizu delivers, offering up a fascinating vision of fusion, synthpop, new wave, and jazz, as articulated with a sharp Japanese sensibility and a dizzying array of early eighties studio magic. From the opening drum notes, of track one, “Ashita”, “Kiren” is a multi-layered adventure through what Shimizu has described as “the dance inside the image of myself.” Listen closely to songs like “Momo no Hana” and “Kagerofu" and you'll hear the rhyme and metre of Japanese prose poetry reimagined as rhythm poems. Across the album, you'll also hear playful improvisations gently corraled into distinct song forms, technology experiments, subconscious rhythms, and his ever-present use of pentatonic scales. It’s also with mentioning the contributions of Aki Ikuta, who provides Linn Drum programming, turntables and studio production assistance on the majority of the album.

That relationship and dialogue delivers some remarkable moments on "Kiren" and, speaking personally, really hits a special, freaked-out dancefloor stride on "Peruvian Pink" and "Shiasate". I'll be putting those ones aside for a DJ set for sure. For me, one of the brilliant things about "Kiren", as with "Kakashi" and "Utakata No Hibi" is how brilliantly Shimizu rides the line between braindance and body music, local culture and outernationality. The work is deeply cerebral and deeply physical, distinctively Japanese, but very much connected to - and well versed in - a broader global musical conversation. Shimizu and his peers were connecting the dots in real-time, and when you think about the research, listening and diligence it took to do that in the early eighties, it's a remarkable thing and well worth celebrating.

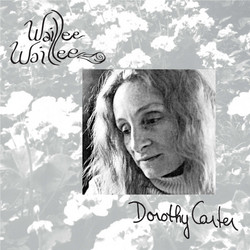

Related products

More by Yasuaki Shimizu

More from Palto Flats

Become a member

Join us by becoming a Soundohm member. Members receive a 10% discount and Free Shipping Worldwide, periodic special promotions and free items.

Apply hereSoundohm is an international online mailorder that maintains a large inventory of several thousands of titles, specialized in Electronic/Avantgarde music and Sound Art. In our easy-to-navigate website it is possible to find the latest editions and the reissues, highly collectible original items, and in addition rare, out-of-print and sometime impossible-to-find artists’ records, multiples and limited gallery editions. The website is designed to offer cross references and additional information on each title, as well as sound clips to appreciate the music before buying it.

Soundohm is a trademark of Nube S.r.l.