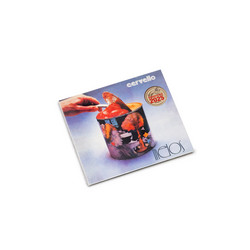

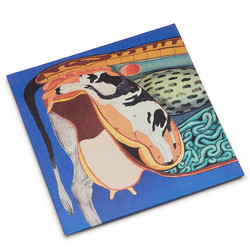

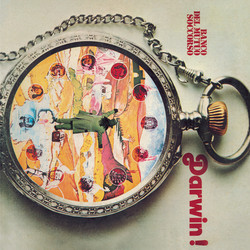

Released in 1975 as a kind of second self‑titled statement, Banco finds Banco Del Mutuo Soccorsoat full creative height, distilling everything volatile in their early work - the classical counterpoint, the jazz‑rock bite, the literary mysticism, the sheer theatrical heft of Francesco Di Giacomo’s voice - into a seamless, long‑form experience. Often treated as a sister text to the 1972 debut, it takes that earlier album’s fascination with metamorphosis, death and escape and renders it with even greater structural confidence: extended pieces that unfurl like short symphonies, powered by Vittorio and Gianni Nocenzi’s duelling keyboards and a rhythm section that can pivot from jazz‑tinged swing to martial stomp without losing clarity.

The record opens in deceptively intimate fashion before plunging into material that is anything but modest. Narration and acoustic guitar sketch the frame in “In volo”, lifting lines from Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso to set themes of holy war and heroism already under erasure; when “R.I.P. (Requiescant in pace)” crashes in, the band stage that medieval brutality as a jazz‑rock battlefield, drums surging, bass anchoring, guitar slipping from warm neck‑pickup bark into full distortion. In the middle, keyboards and piano launch into a frantic multi‑minute solo passage where the Nocenzi brothers braid lines like a New Orleans parade teleported to early‑’70s Rome, the harmonic language classical, the energy closer to a crowded club. When the piece finally collapses back into stillness, the warrior dies, and the text bluntly denies him glory or transcendence, leaving only pain, a knife and the wreckage he leaves behind.

From there Banco dives further into instrumental storytelling. “Metamorfosi” is a British‑school prog epic reimagined in Italian, mostly instrumental, structured around continuous shifts of tempo, texture and emphasis. Voice appears only late, almost as commentary on a process the instruments have already enacted: guitars and keyboards trading themes in increasingly orchestral fashion, the keys handling brass roles, the guitar standing in for strings. The centrepiece, “Il giardino del mago”, stretches past eighteen minutes and is clearly laid out in four movements, a true suite in the classic sense. The narrative follows those who long to abandon reality and live forever in a suspended, enchanted garden, another Ariosto‑derived topos where escape and refusal intertwine; musically, the piece arcs from dream‑slow introductions into more agitated mid‑sections, where riffs and meter changes underline the choice between retreat and confrontation.

What keeps the album from becoming mere showreel is how tightly composition and performance lock together. Banco’s writing leans heavily on classical notions of development and recapitulation, but the playing is hot, physical, rooted in rock timbres and jazz timing: drums punch and feint, the bass works melodically instead of just doubling roots, and Di Giacomo’s voice moves from intimate murmur to full operatic declaration without ever feeling like pastiche. Closing miniature “Traccia”, essentially a concentrated piano statement from Vittorio Nocenzi, functions as both coda and seed, a “trace” that will be picked up and expanded on the next album, reinforcing the sense that these early records form one extended, interlinked project rather than isolated statements.