Elsewhere Music releases Composer, alone - three discs, twelve piano pieces, thirty-four years of Jürg Frey's thinking compressed into moments that feel both eternal and evanescent. The Swiss composer, a founding figure of the Wandelweiser collective, has entrusted these works to Dutch pianist-composer Reinier van Houdt, whose hands understand what Frey's scores only suggest: that silence isn't absence, but presence waiting to be heard.The recordings took place at the Muziekcentrum van de Omroep in Hilversum, with Frey in the room—not as supervisor, but as witness. This matters. These aren't archival documents or dutiful renditions. They're conversations between composer and interpreter, captured in the act of listening to each other listen. Van Houdt, who has collaborated with Frey before (l'air, l'instant - deux pianos, lieues d'ombres), knows the territory. He knows where Frey hides warmth beneath meticulous restraint, where melody surfaces from silence only to dissolve back into it, where a single note can contain an entire harmonic universe if you give it time to unfold.

The program doesn't follow chronology. Instead of linear progression—early works to late, simple to complex—the sequence invites dialogue. Composer, alone (1) (2023/24) opens the set, suspending time in airy expanses where notes hang like watercolor on wet paper. Then we jump back to 1993: In Memoriam Cornelius Cardew, a piece that articulates Frey's minimalist vocabulary with reverence and fragile self-containment. The Klavierstück Arrangement series (1991) follows - skeletal structures that reveal their beauty through what they omit, not what they state. Later works explore different temporalities. Pianist, alone (1) (1998–2004) expands into circular movement, subtle transformations that happen so gradually you don't notice them until you've already changed. Composer, alone (2) balances transparency and suggestion—you hear everything clearly, yet meaning remains elusive, shifting each time you return to it. This is characteristic of Frey's method: music that refuses to declare itself, that asks you to meet it halfway.

Wandelweiser - the collective Frey helped establish in the early 1990s - developed a reputation for extremity. The longest silences. The quietest sounds. The most rigorous reduction. But this misses something essential: Wandelweiser composers aren't interested in silence for its own sake, but in what silence reveals about sound, and what sound reveals about silence. Frey's piano music exists in this dialectic. Notes emerge from quiet, carry their resonance as far as physics allows, then return to the space from which they came. Van Houdt's performance makes this process audible - he doesn't force direction or impose narrative. He lets details emerge at their own pace, trusts the listener to follow. The sound of the piano itself is crucial. Recorded in Hilversum's acoustically sensitive space, the instrument sounds both bare and embracing - intimate without being claustrophobic, spacious without becoming reverb-drenched. You hear the hammer striking string, the string vibrating, the vibration decaying into the room's ambient hum. You hear Van Houdt's fingers leaving keys, the mechanical click of the action. These aren't flaws to be edited out, but essential information about how sound exists in physical space, how music happens through material means.

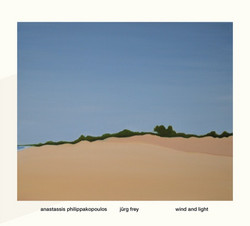

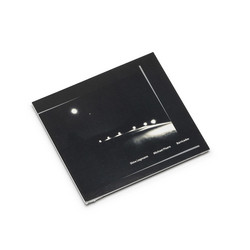

There's a piece Frey wrote in the 1990s, not included here, where the score consists mostly of rests. The pianist sits at the instrument, hands poised, waiting. Occasionally (very occasionally!) a note sounds. The piece isn't about those notes. It's about the space between them, the tension of anticipation, the way your ears adjust to near-silence and begin hearing everything: the room's ventilation, distant traffic, your own breathing. Composer, alone works similarly, though less extremely. These pieces have melodies, harmonies, recognizable musical gestures. But they're surrounded by so much space that you become aware of listening itself as an active process, not passive reception. The sequence is neither heroic nor grandiose. There are no virtuosic displays, no emotional catharsis, no dramatic arcs reaching toward climax and release. Instead: humble monumentality. Music that can inhabit rooms without demanding them. Music that doesn't insist on your attention but rewards it when given freely. This is anti-spectacular in the most profound sense - it refuses the logic of entertainment, of stimulus and response, in favor of something slower, deeper, more contemplative. Frey's own watercolor drawings grace the cover—tender, open, sketched with enough space to let viewers fill in their own associations. The visual aesthetic mirrors the sonic one: minimal means, maximum suggestion. What you see isn't complete, and that incompleteness is the point. The drawings, like the music, are proposals rather than statements, invitations rather than declarations.

For anyone attempting to understand how experimental music has evolved since the post-war avant-garde, how composers after John Cage and Morton Feldman have continued exploring duration, silence, and perception, Composer, alone provides essential evidence. This isn't music that explains itself through program notes or theoretical manifestos. It explains itself by existing, by occupying time and space with patient insistence. Reinier van Houdt has given these pieces the performances they need: clear-eyed, warm-hearted, willing to let the music breathe at its own pace. Jürg Frey, across three decades of work, has built an architecture of silence - rooms within rooms, spaces that reveal themselves slowly, to those willing to inhabit them.