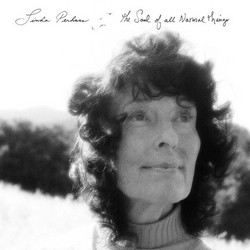

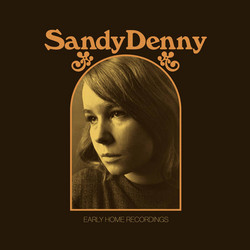

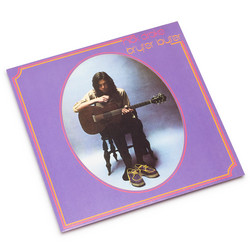

**2025 Stock** Sandy catches Sandy Denny in full, fearless flight, no longer the prodigious voice orbiting Fairport Convention or Fotheringay but a songwriter intent on redrawing the map beneath her own feet. Released in September 1972 as her second solo album, it arrives barely a year after The North Star Grassman and the Ravens, yet the shift is unmistakable: what was once austere and dream-haunted is now wide-screen and tactile, leaning into country colours, brass flourishes and intricate vocal architectures without losing the brittle honesty at the songs’ core. Recorded between late 1971 and May 1972, the record bears the marks of momentum - sessions beginning just weeks after touring her debut, ideas spilling forward before the dust of the road has settled.

The writing on Sandy feels like a series of confrontations with time, autonomy and the fraught luxury of staying still for long enough to look inward. Her originals - from the slow-burning patience of “It’ll Take a Long Time” to the bruised resilience of “For Nobody to Hear” - turn everyday disappointments into carefully faceted studies of character; there is rarely a clean break, only the long fade of feeling learning to survive itself. Songs such as “The Lady,” “The Music Weaver” and “Listen, Listen” occupy a charged space between confession and archetype, their narrators both distinctly Denny-like and larger-than-life, as if she were writing versions of herself that could carry more mythic weight than any diary entry. Even when she steps outside her own pen, as with Bob Dylan’s “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” or Richard Fariña’s “The Quiet Joys of Brotherhood,” she recasts them so completely - multi-tracked vocals inspired by Bulgarian choral music, or a Dylan tune softened into luminous longing - that they feel like extensions of the same interior monologue.

Part of the album’s quiet power lies in the way its expanded palette deepens, rather than distracts from, that intimacy. Producer Trevor Lucas, working with engineer John Wood at Sound Techniques and Island Studios, gathers an ensemble that stretches from Fairport stalwarts Richard Thompson and Dave Swarbrick to Sneaky Pete Kleinow’s pedal steel, John Bundrick’s keys and Linda Thompson’s harmonies. The result is a set of arrangements that slip easily between idioms: a touch of West Coast country-rock here, a brush of British chamber folk there, Allen Toussaint’s brass writing on “For Nobody to Hear” briefly opening a Southern soul window before the album returns to its pale, English light. Harry Robinson’s strings lift “Listen, Listen,” “The Lady” and “The Music Weaver” into a kind of secular liturgy, respectful of space and breath, never swamping the grain of Denny’s voice, which remains the fixed point around which everything else orbits.

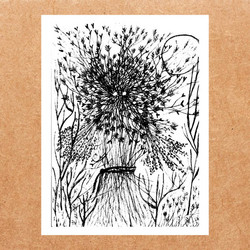

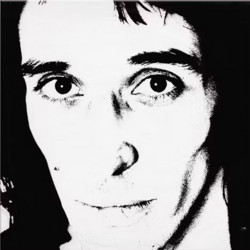

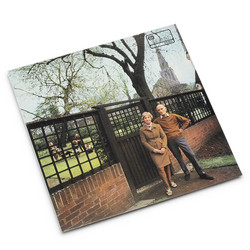

Around the music, the visual and material details of Sandy reinforce the sense of an artist consolidating her public image while quietly unsettling expectations. The original gatefold sleeve, fronted by a David Bailey photograph that would come to define how audiences pictured her, opens to reveal handwritten lyrics bordered by floral garlands drawn by Trevor Lucas’s sister Marion Appleton - a fusion of star portraiture and domestic craft that mirrors the album’s tug-of-war between grandeur and homeliness. On release, Radio 1’s Tony Blackburn singled out “Listen, Listen” as his single of the week, a rare flash of mainstream spotlight for a record whose strengths are stillness, patience and cumulative detail rather than instant impact. Subsequent reissues have added demos and outtakes - including alternate versions of “Sweet Rosemary” and live takes that trace the songs’ evolution - underlining how carefully Denny honed this material while it remained rooted in lived, present-tense feeling.

Half a century on, Sandy reads as both culmination and hinge point: the album where Denny fully claims her status as a writer of modern standards, and the moment before her sound shifts toward the lusher, more overtly nostalgic atmosphere of Like an Old Fashioned Waltz. Its blend of folk clarity, country curvature and subtle orchestration has quietly influenced generations of singer-songwriters who treat arrangement as extension of psychology rather than mere decoration, yet the record itself retains an almost domestic scale, like a series of songs tried out in a front room before being gently, firmly enlarged. Listening now, what registers most strongly is the poise with which Denny balances vulnerability and control: every hesitation, every swell of steel guitar or string section, calibrated to frame a voice that sounds less like it is performing than thinking aloud, tracing the difficult contours of how a life actually feels as it is being lived.