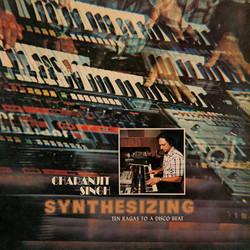

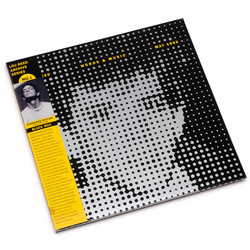

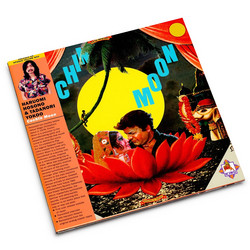

Charanjit Singh

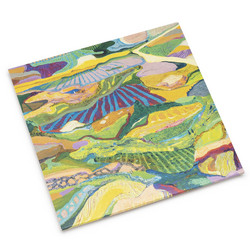

Synthesizing: Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat (2LP)

When Synthesizing: Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat first slipped into the world in 1982, it barely caused a ripple. Cut quickly at Mumbai’s HMV studios and issued without fanfare, the album seemed destined to sit in the blind spot between India’s film industry and a global electronic scene that did not yet exist. Yet what Charanjit Singh committed to tape on those sessions was nothing less than a rewiring of musical time: ten Hindustani ragas, rendered not by sitar, sarangi or harmonium, but by a newly assembled altar of Roland machines - the TR‑808 drum machine, TB‑303 bass synthesizer and Jupiter‑8 polysynth. Working live with just these three devices, Singh programmed the 303 along classical Hindustani scales, set the 808 pulsing at a relentless disco clip, and let the Jupiter‑8 arc melodies over the top, fusing raga logic with a neon, metronomic throb that sounded like the future leaking into the present.

For Light in the Attic’s definitive reissue, that future is finally given the frame it deserves. Released in cooperation with Singh’s estate, Synthesizing: Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat returns as a 2‑LP set, remastered by Johanz Westerman at Ballyhoo Studio Mastering to let the TB‑303’s acid curls and 808 kicks occupy their full physical space. Pressed at Optimal Media and housed in a gatefold jacket that faithfully recreates the original artwork, the vinyl edition restores the album’s tactile, object‑like presence, while a limited “Pearlescent Transcendent Future” colour pressing nods to the record’s almost science‑fiction aura. Inside, a 16‑page booklet gathers previously unseen photographs and new essays that re-situate Ten Ragas not as an odd pre‑echo of Western dance music, but as a product of a restless, technologically curious Bollywood ecosystem. A CD edition expands the booklet to 32 pages, mirroring the same visual and critical depth.

To understand the album’s charge, you have to follow Singh’s path. Born in 1940 and based in Mumbai, he built his career as a versatile multi‑instrumentalist in the Hindi film studios, working with giants like R.D. Burman and Shankar–Jaikishan, and helping to smuggle psychedelia and disco into Bollywood scores as those sounds migrated from London and New York. He was the kind of musician who treated the studio as a laboratory, folding new keyboards, electronic boxes and effects into arrangements that still had to move cinema audiences in single strokes. His hypnotic Transicord introduction to “Dum Maro Dum” in 1971 is only the most famous trace of that sensibility. Touring abroad in the late 1970s and early 1980s, he began returning to India with fresh hardware: synthesizers, drum machines, strange new devices that promised different futures.

By 1982, disillusioned with the constraints of anonymous session work, Singh was ready to stake out his own vision. On tour in Singapore, he discovered the then brand‑new Roland TR‑808, TB‑303 and Jupiter‑8, and saw in them a way to recast raga itself. Where Chicago producers would later use the 303 as a slithering, alien bass voice, Singh treated it as a disciplined melodic instrument, programming its sequence lanes to trace Hindustani modes; the 808 became a bed of precision‑tooled tala patterns; the Jupiter‑8 supplied drones, glissandi and fanfare‑like themes. Tracks like the entrancing “Raga Bhairavi” and the effervescent “Raga Bairagi” unfold as cyclical meditations, each raga stretched over a locked disco pulse until the border between classical improvisation and dancefloor hypnosis collapses. It was, in hindsight, too radical and too contextless a gesture for its moment. The album sank, and Singh drifted back towards private concerts, away from the recording spotlight.

The second life of Ten Ragas began almost accidentally. In the 2000s, Dutch DJ and obsessive record hunter Edo Bouman stumbled on a copy in a New Delhi shop and was stunned by what he heard: music that bore all the marks of acid house - the squelching 303, the four‑on‑the‑floor insistence, the minimalist repetition - but dated from 1982, several years before Chicago would codify the style. Bouman tracked Singh down, reissued the album on Bombay Connection in 2010, and quietly detonated a historiographical bomb. Overnight, Ten Ragas became a cult object, fuelling debates about the origins of acid house and what it means to call someone a “godfather” of a scene they never aimed to join. Singh himself, amused and slightly perplexed, suddenly found himself touring clubs and festivals across Europe, the U.S. and India, performing this once‑forgotten material with Johanz Westerman to thousands of ecstatic listeners.

The essays included in this new edition push back against a simple “lost proto‑acid” narrative. Writers like Arshia Fatima Haq and Jeremy Loudenback (Discostan) point out that for many early champions, Singh’s genius could only be understood through the lens of Western club music, rather than the Hindi film industry that had long been a testing ground for synthesisers, tape experiments and disco orchestrations. Within that framework, Ten Ragas looks less like a freak anomaly and more like a concentrated outgrowth of Bollywood’s experiments in sound and technology. Filmmaker and writer Rana Ghose, who managed Singh in his final years and documented his late‑career resurgence, frames the album as a rare convergence: a centuries‑old classical form, refracted through the most advanced tools available at the time, emerging as a singular artefact that makes new sense in an age of shifting global cultural power.

The aftershocks of Ten Ragas are now everywhere. Artists as varied as Australian psych‑fusion group Glass Beams (who covered “Raga Bhairav”), German electronic duo Modeselektor and Thom Yorke - who singled out “Raga Lalit” on the BBC as an essential listen - have drawn direct inspiration from the record’s coiled patterns and eerie serenity. Perhaps most importantly, the reappraisal has resonated with South Asian musicians and listeners, who see in Singh not a footnote to Western dance music, but a forerunner of diasporic producers reconfiguring classical and filmic references inside electronic frameworks. As Vish Matre of Dar Disku suggests, the album’s true legacy lies less in its supposed status as a precursor to acid house and more in how it cleared space for new music from the diaspora to exist unapologetically on its own terms.

Four decades on, Synthesizing: Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat feels newly contemporary: a spare, glowing lattice of rhythm and mode that sits comfortably alongside today’s most adventurous club music, yet remains anchored in a distinct, local logic. Light in the Attic’s reissue doesn’t just return a cult object to circulation; it restores a story of experimentation, misrecognition and eventual vindication, allowing Singh’s work to be heard not as an accident, but as the intentional, quietly radical move of a musician who treated both classical raga and cutting‑edge circuitry as living, mutable forms.