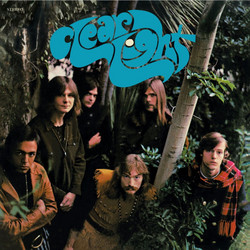

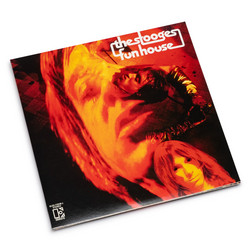

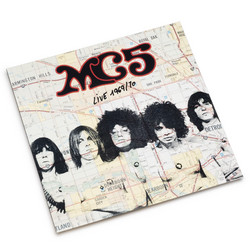

Musically, the record is a wild splice of traditions refracted through Detroit’s late‑60s pressure cooker. Critics and listeners have long noted how the band’s attack prefigures punk by nearly a decade: guitars saturated to the edge of collapse, tempos pushed to careening, vocals teetering between sermon and unhinged rant. Yet beneath the noise, you can hear the group’s deep roots in rock, blues, and even free jazz - Hendrix and The Who in the shredding, the Stooges in the raw propulsion, John Coltrane in the extended, modal blowouts and squall. Tracks like “Ramblin’ Rose” and the title cut hit with garage‑psych ferocity, while “Motor City Is Burning” slows into a bluesy eye of the storm, foregrounding the band’s response to the Detroit riots against a backdrop of smouldering amplifiers. The playing is often sloppy, the mix is “loud or louder,” but that lack of polish is precisely what later generations embraced as the prototype of punk attitude.

Reception at the time was divided to the point of whiplash. Early reviews famously dismissed the record as “ridiculous, overbearing, and pretentious,” while others heard in it a missing link between psychedelia and the nascent ferocity that would soon crystallise as punk. Over the decades, critical consensus has swung decisively: many writers now place Kick Out The Jams alongside The Stooges’ debut and The Velvet Underground’s work as a foundational text, a “snapshot of a transition” where hippie idealism curdles into something more confrontational, sonically violent, and impossible to ignore. Online listener communities regularly hail it as one of the greatest live albums of all time, praising the “pure energy,” “missing link” quality, and the way its rawness still feels ahead of its 1969 timestamp.