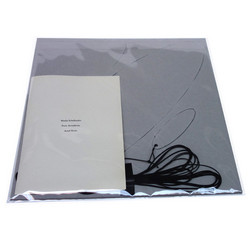

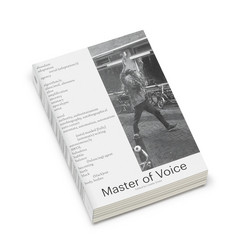

Pietra di Langa extends Enrico Malatesta’s investigation on the oscillatory patterns by stones and ready-made objects. It consists in a solid made of concrete, whose shape has been obtained by silicone casting an actual stone.

With an original text by the British anthropologist Tim Ingold:

“Who says that stones cannot speak? Most of us, if asked. We are pretty convinced that stones are inanimate objects, and that they are therefore incapable of moving of their own accord. And without movement, how can there be sound, let alone speech? We only have to close our eyes, however, for this argument to fall apart. For at that moment, the stone ceases to be an object. It exists in our awareness only as a going-on, as it is caught up in the relations and processes of the world in which it occurs. Even our visual examination of the stone has revealed traces of these movements – of compression, fracture and erosion – from long before there were humans to inspect the consequences. Now, of course, it is we who set the stone in motion. But as the finger-rhythm of ‘de-di-tap’ shows, the stone moves us as much as we move it. The stone, then, resounds. But does it speak? Not if we think of speech as a means to communicate information or ideas. The stone, indeed, has nothing to say. But we know that there’s more to speech than that. For it is by the sounds of speech – by our voices – that we make ourselves heard. Everyone has a different voice, and is recognisable by it. And so, as our experiments have shown, does the stone. It too speaks when provoked, announcing its presence just as we do. ‘Tap … did-didlidl!’” - Tim Ingold, Stone

The project was developed during our stay at Pianpicollo Selvatico, an Italian center for research in the arts and the sciences which is located in the Langhe region, a scarcely anthropized area between the Alps and the Ligurian Sea. It took us a fair amount of time to find a stone that we thought was suitable to be replicated in multiple copies. By exploring the forests, fields and trails around the residency center, we found dozens of rocks which looked and felt pretty much alike, but in the end we stumbled upon one that stand out; first it had the right size and weight to be handled with one hand, it even presented some sort of hooks where to slide in the fingers. Also, it presented a small relief all around a bulge. Andrea Caretto and Raffaella Spagna, artistic couple, geology experts and together with Alice Benessia curators for the art program, explained us that the typical fluid shape of some stones found in that territory comes from them actually being compressed sand. In fact, if one washes them with water, they can break. At some point during this specific stone’s long process of formation, one small section must have come apart, and by being compressed underground, it recomposed again. We were intrigued by how this tiny ‘scar’ would give something as immutable as a stone a sense of temporality and fragility. But in particular, we felt like this one oscillated in quite unpredictable ways and produced the most interesting patterns of sounds. - Attila Faravelli, Aural Tools

Polyrhythmic exercise:

Place the stone on an even surface (a tabletop, the floor, etc.) and take a look at it; observe its shape and superficial texture.

Inspect the points where the stone and the base come into contact.

Place your hand on it and let gravity determine the way it settles. Let the stone shape your hand.

Do not grab the object nor apply intentional force.

Check the stability/instability afforded by the supporting area and the distribution of the stone’s weight.

Allow the hand’s and the stone’s temperature to reciprocally influence.

I

Give a light push to any spot on the stone. Note how it oscillates and the sound that is produced.

Wait for the oscillation to stop, then push again.

Repeat this a few times, turning the stone upside down, choosing different spots where to push, applying various degrees of force, using one finger or the palm of the hand.

While doing this, be aware of:

where exactly on the base area sound seems to come from

how the oscillation fades out over time

the various reactive modes of the stone and the combinations (of position and push) that produce the most interesting results.

II

Give a light push to the stone. Then, just before it stops oscillating, push it again.

Keep the interval between the two pushes as great as possible.

Now, trigger the two oscillations one right after the other, producing a rhythmic pattern made up of two consecutive events.

III

Give a light push to the stone. Then push it over and over again, in order to get a continuous oscillation.

Apply the least possible amount of force (a light pressure can produce a lot of movement). Let the way the stone swings guide you with that.

Finally, while sustaining a continuous oscillation, listen to the sounds and discern between:

multiple simultaneous sounds with adjacent localizations | with separate localizations

resonant | non-resonant sounds

sounds produced by a greater acoustic response of the stone | of the base surface

sounds directly connected to the triggering action of the hand or fingers | peripheral sounds, secondary effect to the hand’s or fingers’ action.

possible correlation between the stone’s velocity and the loudness of the generated sound

how different base surfaces affect movement and sound

how the acoustics of the space affect sound

how the generated vibrations affect other objects on the same surface base.

Enrico Malatesta