We do require your explicit consent to save your cart and browsing history between visits. Read about cookies we use here.

Various

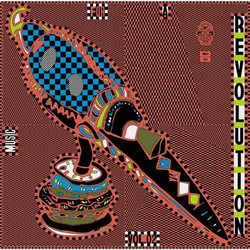

I Am The Center: Private Issue New Age Music In America, 1950-1990 (3LP Box, Clear Yellow)

**Much needed repress** Forget everything you know, or think you know, about new age, a genre that has become one of the defining musical-archaeological explorations of the past decade. Am The Center: Private Issue New Age In America, 1950-1990 is the first major anthology to survey the golden age of new age and reveal the unbelievable truth about the genre. For new age, at its best, is a reverberation of psychedelic music, and great by any standard. This is analog, handmade music communicating soul and spirit, often done on limited means and without commercial potential, self-published and self-distributed. Before it became big business and devolved into the spaced out elevator music we know and loathe today, this was the real thing. From mathematical musical algorithms to airport murder mysteries to Henry Mancini and Bugs Bunny, the connections to mainstream culture run in curious directions. I Am The Center is a knowing, but never cynical overview that invites listeners at last to the mainspring of a misunderstood genre's greatest lights. Many of the biggest names are present ” Iasos, inter-dimentional channeler of paradise music; Laraaji, discovered by Brian Eno playing for spare change in Washington Square Park; and the recently famous JD Emmanuel, icon to a new generation of drone, ambient, noise musicians. Call it what you will” before it was anything else, it was new age.

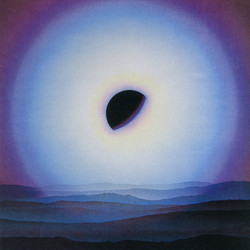

Lovingly conceived and lavishly presented, I Am The Center features stunning paintings by the legendary visual artist Gilbert Williams, and liner notes by producer Douglas Mcgowan, who weaves the words and images of the wizards and sorceresses of new age into a prismatic portrait of music that can finally be recognized for what it is: great American folk art.

It’s hard for me not to get over excited about the current increasing interest in immersive, beat-free music – because ambient was my punk rock. I’m not even joking: I was 15, and nicely stoned, when I heard the first Orb Peel Session on the radio, and it was one of those rare moments in life when all the rules changed. Just as with punk, it felt like everything was up for grabs, and music could be made however you wanted it to be. And throughout my life, whether it was laying sparked out on a beanbag in Megatripolis at Heaven with a brain machine clamped to my face (yeah and what?), or pinned to my seat in the Barbican by the fractal sublime of Wolfgang Voigt’s Gas audiovisual show, ambient music has provided the most intense and stimulating musical moments of my life. Yes, stimulating. There’s a qualitative difference in experience in listening to music that’s incredibly slow. As New Scientist reported last week, our brains lock into tempo sync with the kind of rhythmic music and conversation that form the backbone of modern social experience, which partly explains the pleasures of experiencing rhythmic music en masse: it genuinely does bring us together, in thought as well as action. But below a certain tempo – or with no rhythm – the brain can’t slow down any further and so is no longer led by the music. When that happens your thoughts are free to roam. Which would explain why, as this compilation shows, music that’s free-floating is one of the fundamental bases to which we keep returning, just as we keep returning to the steady pulse of the four-to-the-floor for other reasons. Just like the very best four-to-the-floor house and techno, this is functional music. These tracks were generally made for meditation, or for simple pleasure, and all self-published with little or no hope of commercial gain. The kooks, weirdos, cult leaders and isolated hippies who made them all came by accident or design to the same place – extended ebb or flow of sound that allows the listener to cut loose from the impositions of music and speech that we’re used to. So the harp arpeggios of Gail Laughton (as used on the Blade Runner soundtrack) and Joel Andrews, the piano incantations of the notorious mystic George Gurdjieff with Thomas de Hartmann, the ecstatic synth pads with unending Steve Hillage-style guitar stroking of Aeoliah or the angelic “aaaah”s over rumbles and water sounds of Alice Damon: though they’re made over 40 years, they fit together perfectly.

Unlike Eno’s slightly yuppie-ish vision of ambient sound as “wallpaper”, this is music to turn up loud and let overwhelm you. It’s easy to see how the zoned-out and Zenned-out can get ideas of the eternal from this stuff: the fact that all these people discovered a similar function of music separately must lead them to feel like they’re tapping into something metaphysical and beyond time. And the feeling you can get when fully soaking in this music, set free from rhythm and progression, can, if you’re lucky, give you the sense that it could go on for ever. It’s not eternal music, of course: it just has a very particular effect on your brain, like a drug.

But it’s a drug worth taking – and it is punk in a deeply perverse way. Just like how I felt as an impressionable teenager, you’re forced into a different way of thinking about music and the value of time, and in a time when our time is constantly being stolen from us and a sense of desperation is engendered by our culture, a step into the brainspace of those kooks and weirdos of times past, the active choice of taking two hours plus to enjoy this preposterous, untethered loveliness, feels like a genuinely subversive musical act.

Any consideration of this anthology could just as easily start elsewhere. It could start with the upward twist of Elizabeth Fraser's vocal midway through 'Heaven Or Las Vegas', edges softened by the filigree of Robin Guthrie's guitar FX, or with the rumbling haze around John Cage and David Tudor playing Variations IV in a Los Angeles gallery in 1965, scraping objects and conjuring exotic climes on the turntable. It could start in the swerve of Vangelis' synths mapping the vertiginous transformation of body and urban space in Blade Runner, or in the overloaded, fragile bell and gong tones of Vodka Soap's Un Pyramid Chandelier or James Ferraro's Heaven's Gate. It could start with the opening minutes of waterfall, birdsong and flutey Korg of Oneohtrix Point Never's 'Format & Journey North'. The moods, textures, atmospheres, techniques and philosophy of new age – more on that non-capitalisation anon – extend through huge swathes of popular and more marginal music through the late twentieth century. But – more pertinent to a moment when any era of music can be captured, downloaded, subject to the destructive speeds of network society, and injected into new music – it also haunts contemporary music as a lapsed idyll, a soured dream of peace. Perennially unhip, new age is the disavowed term that makes contemporary music, as a form of technological fantasy, suffering and yearning, possible.

For example, in Emeralds' early releases, the coagulating stormheads of synthesiser and warm melodic guitar suggested a dispersal of bodily anxiety, nerves given up to floating weather currents of sound, but always with the suggested possibility spilling into the atonality and outright noise that the aesthetic defined itself against, and that was well within the reach of their presets. The dream of new age music was shadowed in its own time – the late 60s and early 70s, when the first major New Age labels were set up – by terrible psychic fallout: drugs, psychosis, political despair, the collapse of hippie into another species of cutthroat entrepreneurialism. ("What we’re talking about, basically," says the Malibu circa '68 pusher in Joan Didion's The White Album, "is applying the Zen philosophy to money and business, dig?") The latter was precisely what happened with the codification of the various enthusiasms of the Age of Aquarius – early environmentalism, the mystical strains of Hinduism and Buddhism, indigenous American culture, whalesong, diet fads – into New Age (capital N, capital A, capital all the way down). New Age, as industry, genre and ethos, was born of the counter-culture's burn-out and flight, in the face of Nixon, Altamont and COINTELPRO, into privacy, 'authenticity', the panaceas of 'spiritual development'.

The twins of the emerging New Age industry were, on the one hand, Stewart Brand and Richard Branson with their assumption that a canny, 'ethical' capitalism could produce 'positive' 'change' – and, on the other, Performance and the Manson Family. This fascinating compilation from Light In The Attic manages to weave around this tragic story whilst still implying it for the attentive listener. Almost all of the music here was recorded before new age became the commercial titan of patchouli, crystals and guides to accessing your inner wolf that it is today, or was released on tiny labels mostly run by the artists themselves, available through mail order, circulated among friends, lodged in archives or pressed in tiny editions as vanity exercises. As the extensive sleevenotes by Douglas McGowan note, the composers gathered here weren't captains of industry, but scattered throughout society: jobbing session musicians, cranks, music therapists, dissolute aristocrats, philosophers whose natural habitat would otherwise be the barroom. Gail Laughton, whose 'Pompeii 76AD' later turned up in Blade Runner, played on Looney Tunes and Marx Brothers soundtracks; 'Pompeii...' itself is part of an attempt to imagine ancient societies' music, a lovely, unaffected ripple of strings. Nesta Kerin Crain, who contributes the wonderfully self-explanatory 'Gongs in the Rain', was briefly a baroness before taking up music, becoming a New York antiques dealer and occultist – she is pictured in the sleevenotes in a curious Chinese dress, poised over two huge singing bowls.

Others came to the genre from counter- or high-culture: Joanna Brouk studied at the San Francisco Tape Music Center, then home to Terry Riley and Pauline Oliveros; Don Slepian was a friend of computer music pioneer Max Mathews, and can be heard here playing a synth designed by him; Daniel Kobialka was friends with Henry Mancini and drew on the work of the likes of Lou Harrison and Toru Takemitsu; Laraaji, when he was still Edward Larry Gordon, did conservatoire studies before taking up entertainment, first as a stand-up comedian and then playing the zither as a busker. There was constant overspill between the avant-garde, hucksterism, low life and drug culture, genuine devotion and serious crackpots (consider the proximity of figures like Ron Hubbard or John Lilly, the isolation tank researcher and dolphin communicator, to New Age concerns). The genre was as much of a weird patchwork as the cult it mirrored. Kosmische, the long forms of Indian music (though not necessarily the extended technique), the bouzoukis and pipes of Irish folk, classical guitar as extrapolated by Leo Kottke and Robbie Basho, the more determinedly dull end of 'spiritual jazz,' prog-not-prog instrumental suites like Tubular Bells; but above all, exemplifying the precarious dialectic, the analogue synthesiser.

The plasticity of shape, colour and force of sound available that intrigued late 60s heads, with synthesised sound as the mirror of a conjoined cosmic and inner space – think Morton Subotnick's Silver Apples Of The Moon (a very New Age title), Sun Ra's Moog and Egyptian finery, Mick Jagger's fumbling soundtrack for Kenneth Anger's occult reverie Invocation of my Demon Brother – becomes the medium of a supposedly literal break through to the other side, a vision of a cosmic order in which the biological and angelic are united in a realm of timeless peace. (The notion of sound as a universal medium dates back at least to Pythagoras' "music of the spheres".) Thus something like Iasos' 'Formentera Sunset Clouds', in which pink and blue sweep over each other, momentary resolving as high organ notes, slowing to a movement like summer wind tousling clouds, over recordings of breaking waves. Peter Davison's 'Glide V' layers hovering tones like singing bowls that mock the necessity of change that underpins western melody. The excerpt from Mark Banning's 'Lunar Eclipse' establishes a barely-stirring atmosphere of metallic drones amid which a guitar brushes as if playing itself; the whole thing is possessed of the narcotic slowness of Eduard Artemiev's soundtrack for Solaris. The best acoustic performances here have a similar tone. Wilburn Burchette's solo guitar piece 'Witch's Will' is a soft play with echoes, little eddying riffs and runs that never quite resolve themselves, as if Visions Of The Country-era Robbie Basho had downed some Quaaludes before playing. Kerin Crain's 'Gongs in the Rain' sounds exactly like the title, and bears an odd resemblance to field recordings of Zen stone gardens. Lying hidden amid these tracks is the tension between the intellectual energy invested in these artists' often immensely detailed and specific theologies – the New Age panoply of spirits, rituals, levels of being, pseudo-scientific chronologies tracing alien influence on humans or our descent from the inhabitants of Atlantis – and the reality of men sitting at enormous synthesisers in dirty garages, digestion rebelling against their macrobiotic diets; between the abject flesh and strife-ridden social reality, and the crystalline image of utopia. One can hear much of this compilation as a negative record of the damage inflicted on its subjects, audible as just the slightest trace of melancholy. Daniel Emmanuel's 'Arabian Fantasy', in which two bass synth pulses circle a lamenting chord progression, an arrangement as austere and brooding as Popol Vuh's soundtrack for Aguirre; he later recorded Wizards as J.D. Emmanuel, now a cult record in noise circles. Constance Demby's 'Om Mani Padme Hum' features vocals like wind under the door spilling over organ drones and slumped-on-the-keyboard piano, the whole atmosphere the snowdrift sadness of late Coil. The excerpt from Laraaji's 'Unicorns in Paradise' is a hall of mirrors constructed from percussive zither sucked down by bass pulses, less meditative than caught in a dreadful psychic loop.

At the most significant moments here, it's hard to tell the difference between the still cerulean of meditation and the entropic black of depression. These two moods, as two sides of the same coin, have been the dominant tenor of music in 2013, alongside the acceleration, excess and overload that the culture now takes for granted. Their interdependence was clear enough in Spring Breakers: one can imagine something like Daniel Kobialka's 'Blue Spirals' accompanying the motion-blurred neon stillnesses of that film instead of the acoustic version of 'Everytime' that became its signifier. As the detritus of a past scarred by the conditions of exploitation and defeat that afflict us again now, our part-ironic need for New Age is both symptom and point of critique: the present.

Related products

More by Various

More from Light In The Attic

Become a member

Join us by becoming a Soundohm member. Members receive a 10% discount and Free Shipping Worldwide, periodic special promotions and free items.

Apply hereSoundohm is an international online mailorder that maintains a large inventory of several thousands of titles, specialized in Electronic/Avantgarde music and Sound Art. In our easy-to-navigate website it is possible to find the latest editions and the reissues, highly collectible original items, and in addition rare, out-of-print and sometime impossible-to-find artists’ records, multiples and limited gallery editions. The website is designed to offer cross references and additional information on each title, as well as sound clips to appreciate the music before buying it.

Soundohm is a trademark of Nube S.r.l.