We do require your explicit consent to save your cart and browsing history between visits. Read about cookies we use here.

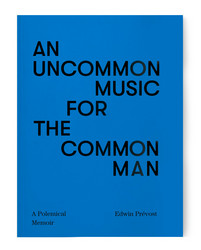

John Tilbury

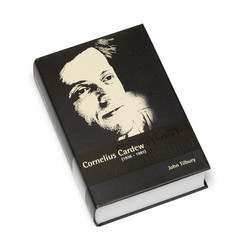

Cornelius Cardew (1936-1981) A Life Unfinished

Hardback cover edition, 1070 pages (!) Cornelius Cardew was a musician of genius for whom Life and Art were as one. He was a radical, both artistically and politically, becoming a tireless activist and uncompromising Marxist-Leninist. Passion and imagination governed all he did: his boldness and humanity continue to intrigue and inspire.

John Tilbury, whose close friendship with Cardew dates from their first concert together, in January 1960, has worked for many years on this biography, and brings his subject vividly to life. In doing this, he has drawn extensively from Cardew’s journals and letters, and obtained first-hand accounts from friends and colleagues. The handling of this material is thoughtful and meticulous. Tilbury is a master story-teller and this particular story is of epic scale and character. We begin in 1932, appropriately on May Day, with the first meeting of his parents. Later, we encounter the intrepid schoolboy and student, who impressed sufficiently at the Royal Academy of Music to receive funds to study in Cologne with Karlheinz Stockhausen. The narrative during this period is delightfully picaresque, a colourful prelude to the years of family responsibilities and extraordinary musical endeavour and achievement (Amm, Treatise, the Scratch Orchestra and The Great Learning). As events unfold, discussion of the music is given due weight, but is never unduly weighty.

Towards the end, there is an implacable gain in momentum as Cardew’s political work makes increasing demands on his time and apparently limitless reserves of energy.

This has been an extremely difficult book to write about. Not the least and certainly the most obvious of its challenges is its sheer size. For over one thousand pages, John Tilbury both chronicles the tiny details and explores the social and philosophical implications of the life and work of British composer and performer, Cornelius Cardew. Writing this book was clearly a challenge for Tilbury himself on a number of registers, a fact that he readily acknowledges in his Preface. For one, he is committed to making a comprehensive biography that gives relatively equal weight to the significant projects, products, and themes of Cardew’s life, which naturally include his unequivocal shift in focus from music-making to politics and the attendant repudiation of virtually all of his previous work in the early 1970s. Moreover, and indicating the intensification of the challenge, Tilbury states that, “[t]hroughout this book I have stressed and insisted on what I regard as the continuity of Cardew’s thought and actions, however much his political comrades have demurred on this issue. They have argued . . . that the qualitative change in his life in the seventies, through a decisive, revolutionary rupture with ‘bourgeois’ ideology, effectively derails my thesis of ‘continuity’” (xvii). And these comrades would surely have had Cardew’s agreement at the end of his life, one expects, which further complicates Tilbury’s project.

Regardless, Tilbury steadfastly pursues this continuity thesis by investing a long list of political rallies, conventions, meetings, and analyses, along with details about party operations, with an importance (and page-count weight) relative to Cardew’s major musical works and associations, including Stockhausen, Treatise, AMM, The Scratch Orchestra, and The Great Learning. The result of this commitment on Tilbury’s part is that music plays at best a secondary role for the second five hundred pages of this text. I could launch immediately into why I think this is a problem, but it’s wiser, I think, to consider my own position in relation to this text first. I was in diapers when Cardew was chanting his revolutionary diatribes an ocean away. I am far from an expert in revolutionary politics, and the dynamics of class relations in Britain—in the 1970s, now, or at anytime—seem dizzyingly complex and ultimately mystifying to me. I know a little bit about music and, no wonder, it’s Cardew’s music that drew me to this text in the first place. To be completely honest, it’s pretty difficult for me to grasp Cardew’s abandonment of the music, and that’s partially what makes him so interesting.

So it’s John Tilbury in whom I need to place a great deal of faith, not so much because he merely proposes the life-long continuity of Cardew’s activity (the decisively revolutionary replacement of art with politics notwithstanding) but because he goes the extra mile to document it at such considerable length and to support it with an impressive amount of careful research. His proximity to Cardew as a friend and colleague during many of the key phases of the latter’s explicitly musical career, and as a political comrade as well (though it’s clear if not explicit that Tilbury’s and Cardew’s political commitments diverged at some point during Cardew’s entrenchment in doctrinaire Maoism), is Tilbury’s greatest resource in this text, not the least because so much documentary material and collegial confidence is available to him. However, as one might expect, there is the pervasive threat that Tilbury is too close to his subject, a threat that is not always effectively staved off. He recognizes this fact, recounting on the first page of his Preface how “one particular friend would enquire, waspishly: ‘John, have you finished your autobiography?’” (xv). He responds in the text, rhetorically, that, “I was not [Cardew’s] Boswell, nor his confidant. We were fellow travellers on a journey which shaped and redefined our understanding of what is still, if only by default, referred to as music” (xv). What underpins Tilbury’s narration of Cardew’s story is the simple fact that, to a large degree, he shared Cardew’s discoveries, triumphs, and failures in the fields of art, of politics, of life, and in the field they tilled where they grew indistinguishably intertwined; his portrait of Cardew is lined with the crevices and shadows carved out by these experiences.

The portrait is quite remarkable. What impresses me the most is that Tilbury underscores how Cardew’s musical life is fundamentally about his sustained attention to the social dynamics of music-making, and to extending how a work or performance of art can inflect and emphasize the social relationships that are the basis of all artistic practice. Indeed, if Cardew’s mentor and colleague, John Cage, served to expand our conception of what a musical sound can be, then Cardew made similar strides in elucidating the social implications of music-making, especially within the art world of Euro-American concert music that was, for the most part, his milieu. His fraught involvement in Cologne in the late 1950s with Stockhausen and other European serialists and the stifling strictures their work placed on interpreters provoked his rigorous research into extended and graphic notation, culminating in his magnum opus, the 193-page Treatise, as beautiful and complex visually as it is surely difficult to interpret and perform. Tilbury’s detailed analysis of this incredible work, which both isolates technical details and interprets the philosophies of composing and interpreting it, is especially valuable and reaffirms how impressive Cardew’s achievement is. Simply put, anyone interested in graphic notation—as a researcher, a practitioner, or otherwise—would be remiss to ignore this part of the text.

Concurrent with the completion of Treatise was the beginning of Cardew’s involvement in 1965 with AMM, the radical improvisation ensemble that, at its inception, included Keith Rowe, Eddie Prévost, Lou Gare, and Lawrence Sheaff. While Cardew’s participation was prompted foremost by his search for non-classically trained musicians to play Treatise, their “meta-musical” collective improvisations represent some of the most nourishing musical experiences in Cardew’s career primarily because they embodied the social relationships between group members and, indeed, the connections between the musical and non-musical world in a concrete way:

The commitment to improvisation, the insistence on its relation and relevance to the non-musical world, if such a separate world exists, was shared by all the members of the AMM, whose radical mission was to recognise the “musical composition of the world” no less. “My attitude is that the musical and the real worlds are one. Musicality is a dimension of perfectly ordinary reality,” Cardew wrote. (312)

Such a passage presages other major milestones and turning points—musical or not, should a distinction be made—in Cardew’s life by emphasizing how the relationships between people and with the world in general are the foundations of Cardew’s ostensibly “musical” world view.

Notably, by founding and serving as the senior figure—Tilbury resists calling him the outright leader—of the legendary Scratch Orchestra, the huge social and musical experiment in which trained and untrained musicians created and presented music and performance art in a collective and non-hierarchical way, Cardew extended his musical persona beyond the circumscribed social dynamic (at least in Euro-American modernism) of composers and performers. Peeling away the investitures of art-discourse authority, Scratch members, whether trained or not, equally contributed compositions and the interpretations thereof as part of outlandish and unconventional presentations. This was carried out with a utopian, sign-of-the-times fervour that Tilbury captures beautifully through the careful deployment of numerous anecdotes and commentaries from Scratch members that are interwoven with Tilbury’s lovingly personal reminiscences. With limited documentation of the Scratch Orchestra in general, Tilbury’s chronicle of its history is most welcome.1 Insofar as the group had dozens of members, each with a varying nature and degree of commitment to the Scratch ethos and attendant centrality within this narrative, the best that Tilbury can do is to create a kind of gestalt portrait, noting readily that shaky memories have led to varied and, in cases, contradictory accounts of particular Scratch events. In a sense, to question the facts is to miss the point a bit, as Tilbury’s account evokes nothing less than the spirit of this totally original, Cardew-inspired project. This history alone, by documenting a rather enigmatic and slippery musical and social phenomenon, makes this biography very valuable to anyone interested in Twentieth Century experimental music.

However, if the Scratch Orchestra and Cardew’s contributions to it, especially The Great Learning (to which Tilbury devotes a chapter), represent an apotheosis of Cardew’s synthetic reappraisal of life and/as art, Tilbury is quick to note (and long to describe) how the internal forces that led to its demise served to provoke Cardew’s revolutionary political conversion. Here, I detect a bit of melancholy—“regret” would be too strong a word—in Tilbury’s writerly voice. Though Tilbury’s own story is deeply implicated with Cardew’s and the Scratch Orchestra’s during this period, he seldom refers to his own role directly; he was one in a group of Scratch members who sought the politicization of the group and to make the group more “relevant” by shedding its “bourgeois” art-making proclivities. I sense that, for both the author and many of his interview subjects, the dissolution of the Scratch Orchestra feels like a painful memory, one that casts a bit of a pall over the remainder of the book (which is to say, the second half!). This most likely has to do with an ongoing ambivalence, on Tilbury’s part, about the ultimate costs and benefits of Cardew’s politicization, one that he can’t seem to shake despite his previously noted commitment to the continuity of the overall trajectory of Cardew’s work.

From the outset, Tilbury acknowledges his problematic position in relation to this part of Cardew’s life and work in particular, warning that some readers may mistakenly consider him to be acting as an apologist for what may seem like overly zealous and naïve choices and actions on Cardew’s part. Most notably, in Tilbury’s chapter on Cardew’s jargon-laden and relentlessly positivistic (and quaintly—if not ridiculously—titled) Stockhausen Serves Imperialism (1974), he maintains an almost mannered tone of neutral exegesis. Tilbury patiently wades through Cardew’s overdriven ideological arguments, even-handedly defending what he considers to be the solid foundation of arguments no matter how far-fetched and misdirected their surface details may be. In the end, if Tilbury fails to convince that Cardew’s political text sits alongside his great works like Treatise, AMM, and The Great Learning (not that he ever sets out to do so), he at least has convinced me to revisit parts of Stockhausen Serves Imperialism, a book that on previous occasions I have literally thrown down in exasperation. This is no small feat on Tilbury’s part!

Now, as I’ve mentioned, I am ill-equipped and, I’ll admit, rather reluctant to assess the large segment of the book devoted to Cardew’s primarily political work. For example, if it holds value for researchers of the history of revolutionary politics in Britain then I wouldn’t be able to say how much. The best that I can do is to consider these chapters from a lay-reader’s perspective and in the context of the musical career that makes Cardew an interesting subject to me in the first place. At the end of the day, I find much of the writing on Cardew’s political years to be quite dry and rather inaccessible. While I’m sympathetic to Tilbury’s goals, it doesn’t play out very well from the simple point of view of a reader actually trying to get through a tome of this size. At a guess, most readers who are coming to it with an interest in Cardew’s music will simply skip the chapters on the later, political years. (Though it’s admittedly not an entirely accurate comparison, I’ve mused about the absurdity of Charles Ives and William Carlos Williams biographies that devote half of their content to insurance and medicine, respectively.)

As I’ve described, Tilbury shows an unflagging commitment to chronicling an entire life, a task that demands his fervent faith that all of the thoughts, actions, and outcomes from the seemingly disparate and perhaps contradictory parts of Cardew’s life are worth telling in detail. In this way, and mirroring his subject’s work throughout his life, Tilbury pays no heed to—and, perhaps, implicitly critiques—the dictates of commerce, or of artistic and intellectual fashion. His commitment to the totality of his friend’s story trumps any need to produce a notably “readable” (which may, ultimately, be a euphemism for “saleable”) text. Like the utopian and visionary ideals that informed virtually all of Cardew’s work, in one way or another, this commitment is underpinned by Tilbury’s own inspiring philosophy of life and art—something he brings to bear readily on his own magnificent music-making. However, it also quickly provokes the pragmatic question, “But who is really going to read (all of) it?” Sadly, given the monumental nature of the work, I’m afraid that the answer will be, “Very few.”

Nevertheless, as I see them, the chapters that document Cardew’s key musical activites, from roughly 1959 to 1971, are essential reading for anyone interested in Euro-American modernist music in general, and the social implications of such music in particular. Despite John Tilbury’s continuity thesis, it is this history, prior to Cardew’s revolutionary break from his musical life, which tells this reader the most interesting story of a man and an artist who was, by any standard, a true original.

Related products

More by John Tilbury

More from Matchless Recordings, Copula

Become a member

Join us by becoming a Soundohm member. Members receive a 10% discount and Free Shipping Worldwide, periodic special promotions and free items.

Apply hereSoundohm is an international online mailorder that maintains a large inventory of several thousands of titles, specialized in Electronic/Avantgarde music and Sound Art. In our easy-to-navigate website it is possible to find the latest editions and the reissues, highly collectible original items, and in addition rare, out-of-print and sometime impossible-to-find artists’ records, multiples and limited gallery editions. The website is designed to offer cross references and additional information on each title, as well as sound clips to appreciate the music before buying it.

Soundohm 2023. All rights reserved. See our privacy and copyright statement for more information.