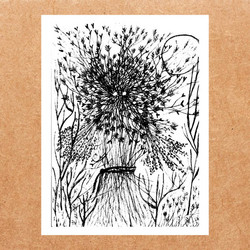

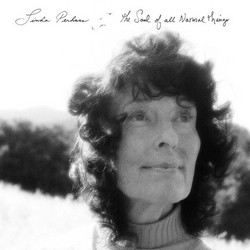

There are “lost classics,” and then there are records like Marana tha - albums so vanishingly rare that for decades they functioned more as rumour than as music. Recorded in the early 1970s by American singer-songwriter Megan Sue Hicks while based in Australia, this lone LP became one of those whispered names among psych-folk obsessives, an almost mythical entry on want lists precisely because almost no-one had actually seen, let alone heard, an original copy. Stories circulated about a tiny private pressing, songs with a devotional undercurrent, and a voice that somehow threaded together the unguarded intimacy of Vashti Bunyan with the harmonic sophistication of Judee Sill. The re-emergence of the album in the reissue era finally lets that legend be tested against the grooves - and, unusually, the music more than matches the mythology.

What strikes first is how unforced Marana tha feels. Rather than lean into the theatricality or cosmic sprawl that “psychedelic folk” can sometimes imply, Hicks works in miniature: closely-miked vocals, lightly picked acoustic guitar, discreet additional colours that drift in and out like passing weather. Within that modest frame, though, she smuggles in all kinds of eccentricities. Melodies take unexpected turns, cadences hover on unresolved chords a bar or two longer than expected, and devotional or quasi-spiritual images surface not as dogma but as flashes of private revelation. The songs feel as if they were written in a small shared house at the edge of town, late at night, half for friends and half for some unnamed presence that might or might not be listening. It is music with clear folk roots that also resists the tidy “singer-songwriter” tag, too slippery and self-contained to slot neatly alongside the Laurel Canyon mainstream.

Hicks’ voice is the record’s quiet axis. There is none of the showy vibrato or studied fragility that often defines cult folk records; instead, she sings as if thinking aloud, confiding more than performing. That restraint allows tiny details to land with disproportionate force: the way a phrase lifts unexpectedly into head voice, the soft edge on a consonant that turns a line from description into invocation. Lyrically, she moves between plainspoken relationship scenes and more impressionistic, sometimes biblically inflected imagery, but the tone remains consistent: a kind of clear-eyed tenderness that refuses both cynicism and naive escapism. The title itself - an old Aramaic expression often translated as “come, Lord” - hints at transcendence, yet the album’s most affecting moments are grounded in small human negotiations with doubt, trust and disappointment.

Part of what makes Marana tha resonate now is how thoroughly it sidesteps the commercial logic of its era. Released in a tiny run and barely promoted, it was never built for radio or extensive touring, and that lack of compromise is audible in its pacing. Songs are allowed to breathe at unhurried tempos; instrumental passages are brief but telling, hinting at jazz or chamber textures without ever turning into showpieces. The album plays like a single continuous mood, gently shifting between inner rooms rather than jumping from potential single to potential single. In the age of the playlist, that coherence feels almost radical: here is a record that asks to be heard in sequence, as a single extended exhale.

The modern reissue of Marana tha restores not just the music but the context that once made it nearly invisible. Carefully reproduced artwork and detailed notes place Hicks within a loose constellation of early-70s Australian and expatriate artists, many of whom recorded one or two albums before slipping out of view. Yet even in that company, this LP stands apart. It is deeply of its time - suffused with the era’s spiritual searching, its turn toward small-scale, back-to-the-land living, its suspicion of big-industry machinery - but it also feels curiously outside time, as if it had been waiting in a quiet room for listeners who might finally be ready. Heard today, Marana tha is more than a collector’s prize: it is a fragile, fully realised world, modest in scale but expansive in emotional reach, a reminder of how much can be carried by one voice, one guitar, and a handful of songs that truly mean what they say.