Paul Bley

Touching & Blood 1965/66

Paul Bley is a master of the piano trio. He showed new and different ways of exploring the complex triangular geometry of what has arguably become jazz’s signature formation. Bley’s early recording with Charles Mingus and Art Blakey promised great things to come. He emerged more fully as part of Jimmy Giuffre’s innovative trio with Steve Swallow, but it was with his own trios of the mid to late 1960s, with drummer Barry Altschul and bassists Kent Carter and Mark Levinson, that he really began to unfold an individual vision that is best sampled in Touching and in the live recording he made in Haarlem, The Netherlands. These are modern jazz at its most searching. - Brian Morton

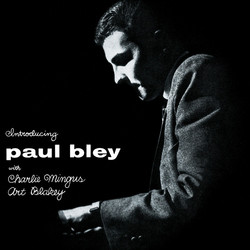

Jess Stacy is best known for his epic solo on “Sing, Sing, Sing” at Benny Goodman’s famous 1938 Carnegie Hall concert, but Stacy is also significant in being the first pianist to work in what has become a ubiquitous formation in modern jazz, and in the last decade more than ever. For fans of the art, the jazz piano trio reached its pinnacle of perfection with Bill Evans’s Village Vanguard performances of late June 1961, with the trio of Scott La Faro and Paul Motian. In 1982, Stacy was lured out of retirement – he’d walked out on music after a woman spilled beer in his lap – for one last performance. Evans had died shortly before, and it seemed that the piano trio literature had left its golden age. And yet there was a whole second line of development within the same format that until relatively recently has been overlooked and undervalued. Paul Bley is the Trotsky of modern jazz, its prophet of permanent revolution. He was a leading, though because white and Canadian often unacknowledged, figure in the creation of the Jazz Composers Guild in 1964, which became the laboratory for new experiment in jazz, unfettered by entertainment models, Broadway tunes and corporate structures. Bley made his first recorded trio performances with Charles Mingus and Art Blakey on the bassist’s debut label, and already sound different: angular, unpredictable, with a fierce brand of lyricism. His first celebrated trio was with clarinettist Jimmy Giuffre and bassist Steve Swallow. They made several ground-breaking albums of a species of chamber jazz previously unheard: Fusion, Thesis, Free Fall and the live recordings from Stuttgart, Bremen (on hatART/hatOLGY) and recently from Graz, Austria released on ezz-thetics 1001.

Almost more significant, in terms of Bley’s individual development, was his participation in Sonny Rollins’s 1963 RCA recording Sonny Meets Hawk. Pat Metheny has described Bley’s solo on “All The Things You Are” as “the shot heard around the world”. Over the remainder of that decade Bley emerged as an improviser of astonishing depth and complexity. He worked in a hard, percussive vein very different from the independently floating lines that Bill Evans favoured. He retained more of the abstractions of bop but also incorporated elements of minimalism, nonfunctional harmony and pure sound-colour, often with an African-sounding quality. Listen to “Blood” and “Mister Joy” on the Haarlem recordings here and there are striking similarities with the work of Abdullah Ibrahim. The earlier of the recordings “revisited” by ezz-thetics is Touching, again made for Mingus’s Debut, but recorded in the autumn of 1965 in Copenhagen. It remains a modern classic. Not the least individual aspect of it and of Bley’s music at this time is that almost all the compositions on the record were by women who had been both creative and life-partners. Bley met Karen Borg when she was selling cigarettes at Birdland. She changed her name to Carla, and then to Bley when they married, and though they divorced shortly after, she retained her married name professionally. The other sharer was Annette Peacock. Bley had encouraged Carla to take up composition and she quickly evolved an innovative, unique style that blended avant-garde practices with theatre and a measure of the Third Stream sensibility that was current at the time. Peacock had, or was instilled with, a similar sensibility. A few years before his death Paul Bley told me that three distinct persons became one in the music on Touching. “There’s this damned obsession with ‘the composer’ over her and ‘the player’ over there. There’s also an obsession

with originality and ownership, like, this music isn’t authentic if I didn’t write what I play myself. It isn’t like that. The music doesn’t exist until it’s played. I’ve no time for head music”. Nothing could be further from that than the music on Touching. The title, taken from Annette Peacock’s most beautiful song, is absolutely apposite. This is music about contact as well as emotion: “touching” has those two meanings in English. It is about a coming-together of abstraction and physical presence, the mathematics of the melody becoming reified – not rarified – in air. It’s unwise to play too much with titles, but “Both” and “Closer” (the latter a rare Paul Bley original of the time) are equally significant signals. Bley had assembled a highly inventive trio to accompany him. Bassist Kent Carter often sounds as if he is playing cello and drummer Barry Altschul, far from being a mere time-keeper is the most challengingly musical percussionist of his time, with a style very different from the current Elvin Jones, Sunny Murray, Andrew Cyrille approach. If Touching is the embodiment of two different creative partnerships, it is also a perfect illustration of the unique dynamics of the trio, which unlike any larger or smaller format militates against conversational indulgence or solitary musing. Listening simultaneously to two different voices and to the musical imaginings of two different composers exerted a revelatory pull on Bley and he delivered an album of lasting power, that deserves to be considered – though rarely is – one of the most important of its era.

Live – and I can personally attest to this – the group was stunning. I heard them when still a schoolboy and the memory will never fade. The group that recorded in Haarlem, Netherlands (not Harlem, as some disco - graphies insist) was slightly different from the Touching group in that Mark Levinson had replaced Carter in the bass role. One point in common between Bley and Evans was their shared wish to keep a regular group together, ideally in Evans’s case for three years, though tragically his greatest group was foreshortened by the early death of Scott LaFaro in an auto accident. Bley worked hard to integrate Levinson’s punchier and less obviously singing sound. They’d recorded Ramblin’ and Blood in European studios some months prior to the Haarlem date and the group that came together that November day was in fierily exuberant form. There is no performance in modern jazz that lifts my spirits more than “Mister Joy”. It and “Blood”, both Annette Peacock compositions, were to remain in his repertoire for some time and appear on other albums and live recordings of the period, with different groups. But they were never bettered here, and for my money, the art of the jazz piano trio reached its peak in Europe in the middle 1960s. That’s not denigrate Bill Evans or belittle the transcendent of the Village Vanguard sessions, just to state an evolutionary fact. Listening to Paul Bley, open-mindedly, will change your heart and your hearing. - Brian Morton, January 202